Xenophobia and Rebellion in Hungary

By: Javier Bauluz

A large crowd can be seen at the end of the railroad tracks. The rumor spreads by word of mouth. The Hungarian government is about to close the barbed wire fence along the border with Serbia. The refugees ask themselves if they should risk trying to cross the only route still open, the train tracks.

Staying far enough away to avoid police, they search for information on their cell phones. The majority do not want to be fingerprinted. They all know that under the Dublin Regulation, an asylum seeker fingerprinted and registered in one European country cannot live or seek asylum in another, and must be deported to the first country. No one wants to live in Hungary. The Syrians wonder if Germany will meet its promise to welcome every refugee who goes there.

After much debate and doubts, the majority decides to cross the train tracks. No policemen are in sight, Serbian or Hungarian. They speed up and walk between the wire fence on either side of the rails. Many make the “V for victory” sign with their fingers. “We are in Europe. We did it.” And they keep walking.

Other groups send youths to scout the fence and find a place where they can cross it, unnoticed by any police. Everyone knows that at the gas station in nearby Röszke they can find crooked taxi drivers who charge a fortune to drive them to Budapest.

Night falls and several groups, mostly made up of young people, walk into corn fields and head for the fence, guided by their cell phone GPS. Everything is now whispers and tension. Some manage to cross the fence, but soon realize it was not worth the risk of getting cut on the razor wire because they could have simply crossed the train tracks and then hid along the sides.

Hungarian police detain and handcuff some of the fathers in front of their frightened children after spotting them among the trees, according to other photojournalists.

Most of the refugees continue walking on the tracks, but one mile into Hungary they are stopped by police and forced to sit in an open field. Several Hungarian volunteers struggle to distribute water and something to eat. Hundreds more arrive, and soon the buses the refugees are “invited” to board are not enough.

Dozens must spend the cold night in the open. Exhausted mothers sleep on the damp dirt, hugging their children to keep them warm. The field has turned into a garbage dump. A helicopter flies overhead, using its powerful spotlight to search the nearby forests.

The refugees are bussed to a registration center with military tents and surrounded by wire fences. Hundreds of people, including many children, are locked up there every day, under horrible conditions, until their papers are processed.

Several hundred skinheads wearing army boots and flying the flags of right-wing groups head to the border, accompanied by police, and insult the frightened refugees who have not yet crossed. The refugees keep a cautious distance from the slogans and chants promising to block “the Muslim and foreign invasion.”

“I thought that in Europe we would not be treated like this,” says a disillusioned Syrian engineer at the train station in Szeged, from where he and his family are traveling to Budapest.

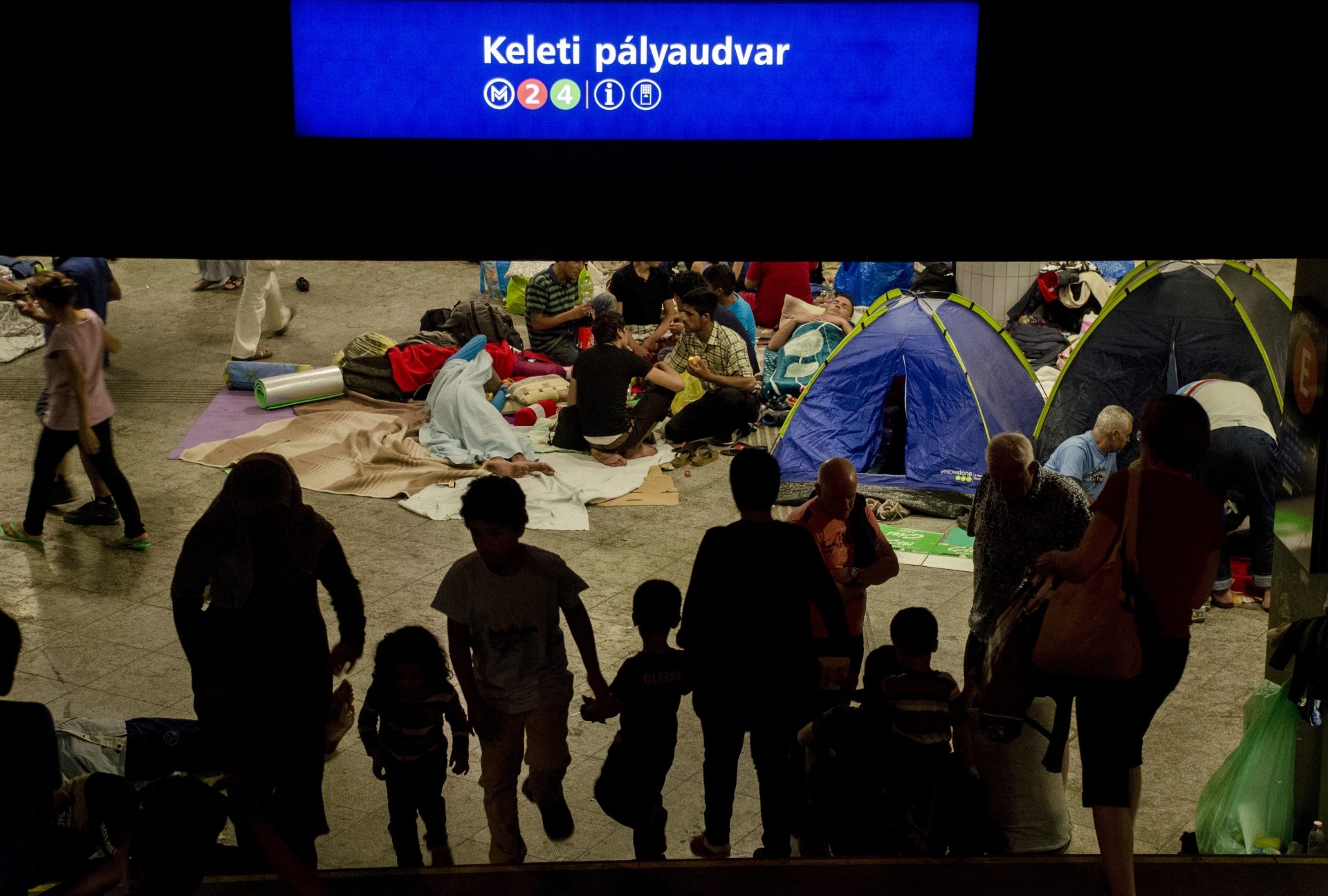

Hundreds of refugees have started a massive protest in the Hungarian capital, desperate after the government stops the trains to Austria. Several thousand take shelter in the overcrowded train station and adjoining metro station. Hundreds of families with small children sleep on the floor or in small tents. They have been trapped there for several days, and the tensions grow. Young refugees with megaphones organize meetings in the plaza, while parents display signs saying they want to move on to Germany. Each day, more than 1,000 new refugees arrive.

A few Hungarian volunteers bring them food, drink and some clothes. There’s only 10 portable toilets for the hundreds of people who wait in orderly lines, standing in urine that overflows from the full toilets.

Xenophobia, extensively promoted by the far-right government, is rampant throughout the country. The anti-Muslim speeches of the president, a “defender of Christian civilization,” has infected a big part of the population. Thousands of soldiers and police have been sent to “defend the border from the invasion.” At a multinational hamburger chain near the station, Hungarian youths dressed in black uniforms and boots seek out refugees and throw them out. Twice, journalists see two Hungarian youths, raging with patriotism, wade into large groups of Syrian refugees and insult them – not realizing the risks they ran. No one tried to attack them.

The looks and gestures of scorn and superiority also have been directed at the journalist, by the bus drivers who refuse to open their doors as they laugh, the shop girl who looks disgusted when serving a foreigner, the taxi driver who refuses to pick him up or the barber who refuses a haircut for a colleague. Other journalists report they were punched when they tried to board a bus.

One morning, while almost everyone sleeps under blankets on the floor of the metro station, the journalist watches a middle-aged, charismatic Syrian man approach each one of the groups and tell them, “Wake up! Let’s go! Up! If they don’t let us on the trains, we will walk to Germany. No one has the right to stop us. We don’t want to be here.” The people look at him, surprised but smiling. The man continues walking and talking. When he spots a group of teenagers dozing under blankets, he pulls them to their feet and urges them to rebel. Little by little, people stand up, and two hours later an unarmed “army” of more than 1,000 is ready for the grand march.

There are men missing legs and walking with crutches, grandmothers with their grandchildren, men in wheelchairs, women, young people, mothers, fathers and children, many children. They all walk out of the train station and head to Germany. They are too many for the sidewalk, but they take up only one lane of the street, to avoid blocking traffic.

Many of the Hungarian citizens of the European Union look at them with surprise and scorn. Very few applaud them as they walk quickly, firmly, with their heads held high, crossing streets, avenues and bridges. They carry nothing but their small backpacks, their determination and their hope.

Dozens of police soon flank them. They don’t know what to do. There are many journalists and cameras. They surround the refugees on the outskirts of the city, but eventually give up and only keep the traffic moving on the highway.

On the Grand March to Germany, the photojournalist reunites with several refugees he met on the train trip in Macedonia, the roads of Serbia and even the Greek island of Kos. The cardiologist, the engineer, the father who held his laughing child against a window, and the grandmother on the train – he had met her again crossing into Hungary. Smiles and quick hugs, to keep up with the quick pace.

After several miles they walk past a military barracks displaying large portraits of officers from the former Austria-Hungarian empire. Guards on duty look on with disdain.

They continue forward under a suffocating heat. They reach a supermarket and hundreds of refugees go in to buy water. At the door, an elderly Hungarian hands out grapes to children from a small bag in his leathery hands. A bit further on, a woman with a dog waves at them and wishes them good luck, her emotions barely contained. From passing luxury cars come insults and obscene gestures, which go unanswered.

A husband and wife stop their car on the highway, open the trunk and start to hand out food they just bought for the marchers. Further on, a group of neighbors offer fruit and bottles of water. Everyone is grateful, but no one stops because they don’t want to lose their place on the march.

From time to time they stop, to rest in the shade of an overpass and wait for the weaker refugees so they are not left behind. The sense of community and unity gives them the energy to continue. Some of the reporters, seeing the tired fathers and mothers, put aside their cameras and carry children on their shoulders. A car picks up the grandmother from the train, two pregnant women, two children and four photojournalists – two of them riding in the trunk.

After several hours on the road, some walk barefoot on the hot asphalt because their shoes have caused blisters, but they and their dead-tired children never stop.

Night is falling when they reach a highway rest stop with a shop. They don’t stop. Two or three miles later, when it’s pitch black, they move to the shoulder, park the strollers and drop exhausted among the bushes. Most of the children fall asleep immediately, while the adults cure their blisters with the help of volunteers who arrive with bandages, anti-inflammatory pills, water, blankets and food. The only lights belong to the cars that zip by on the highway, and the dozens of police cars parked along the shoulder.

Most are sleeping when several buses arrive. What was impossible before the rebellion and the march is now a request from the authorities. They want to take the refugees to the border with Austria. Several people board the buses, but soon there’s a decision that the government is not to be trusted, that there’s no guarantee the buses will not take them to camps surrounded in barbed wire. They did just that a couple of days before, tricking people onto a train that was supposedly going to Germany but instead took them to an internment camp.

“Everyone or no one,” is the watchword. Everyone gets off. After tough negotiations with the Hungarian humanitarian organization that coordinated the buses sent by the government, there’s a decision to send just one bus to the border. The rest will wait until there’s confirmation of their arrival.

There’s also word that dozens of buses are preparing to pick up everyone at the Budapest station.

At the capital, the journalist finds the station almost empty and hundreds of people outside boarding buses bound for Austria. Big families, elderly people, the handicapped, men and women fill the seats while scores of anti-riot police ring the area.

It’s five in the morning, and there’s no one left in the plaza. The Great March achieved the goal of changing “policy.”

Shortly afterward, the Hungarian border with Serbia was closed and the refugees took a different route to Austria, through Croatia and Slovenia.