Stories: María Sánchez Díez. Illustrations: Javier Güelfi

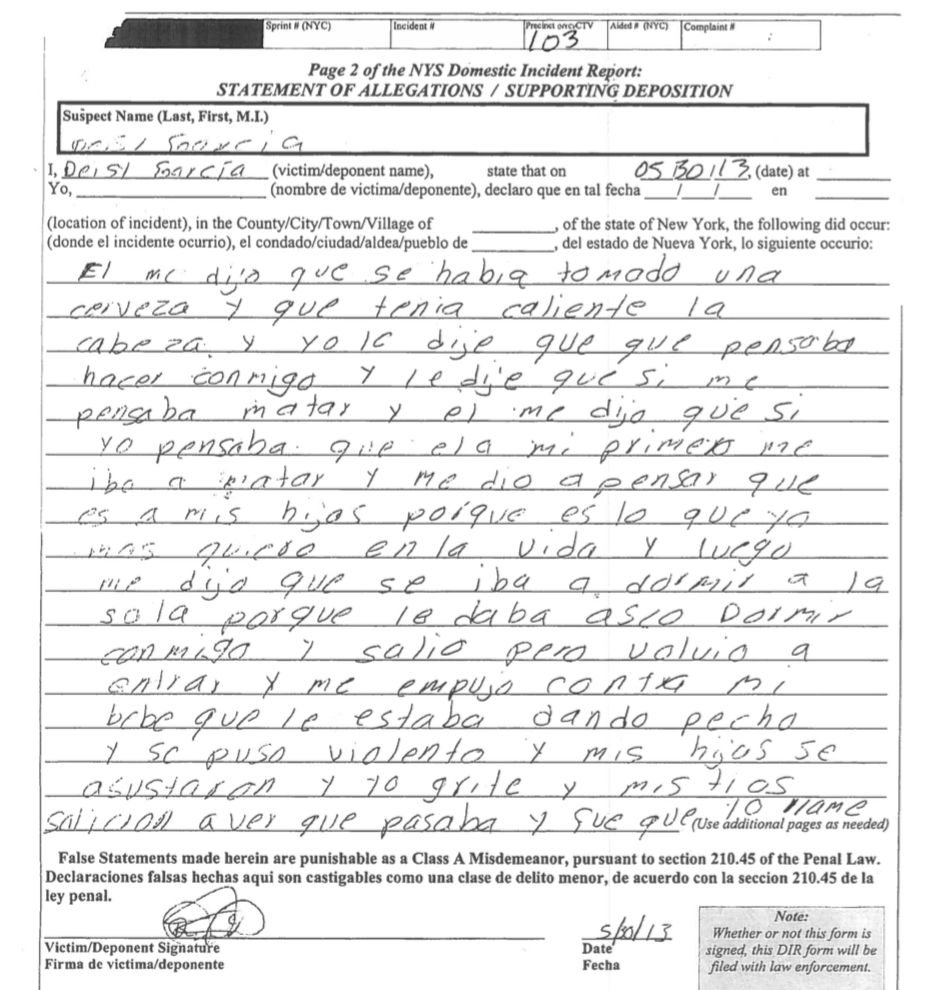

He told me he had had a beer and that he was boiling over and I asked him what he was thinking about doing to me… I asked if he was thinking about killing me and he told me yes. I thought that first he was going to kill me… and then I thought it’s my daughters because it’s what I love the most in life.”

Deisy García jotted down these words in Spanish in the first domestic incident report that she filed with police on May 30, 2013, obtained by Univision Noticias.

The 21-year-old undocumented immigrant from Guatemala was scared. Her husband, Miguel Mejía-Ramos, regularly beat her in the Queens apartment they shared with their two young daughters and her aunt and uncle. This time, though, his threats drove her to call 911 and to file the report that ended up at the 103rd Precinct in Jamaica.

The officers there reportedly did not translate her words.

Deisy García’s report

On Jan. 18, 2014, eight months and another emergency call to the police later, Mejía-Ramos came back late after work to their home on Sutphin Boulevard. García and their daughters were sleeping in the rear room.

Court documents provide this account: Mejía-Ramos had been drinking at a friend’s house. He took his wife’s phone and saw a picture of her next to another man. Consumed by jealousy, the 29-year-old grabbed a kitchen knife and stabbed his wife, as she screamed “Why?” She ran out of bed to another room, where she collapsed and died.

Then he walked back into the bedroom where his 1-year-old daughter, Yoselin, slept as 2-year-old Daniela sat up, awakened by her mother’s screams.

Mejía-Ramos put Daniela back to bed and gave her a kiss before stabbing her three times. Then he did the same to the baby.

He later told police he was going to flee with the children – but realized he didn’t have car seats for them.

“First I saw Deisy, covered [with a blanket] on the floor, and I thought about the girls. I thought that he had taken them with him,” said Romeo Chuc, Deisy García’s uncle. “But then I entered the room. I saw a lot of blood on the walls. The two girls were dead in the bed, in an embrace.”

Deisy García’s last picture

After trying to commit suicide by stabbing himself in the chest and hanging himself with a strap, Mejía-Ramos took $240 from his wife’s diaper bag and hit the road in his white van. Mejía-Ramos, who was arrested in Texas in his way to Mexico, confessed to the killings and later pleaded guilty. He’s serving 40 years at Attica.

The translation of García’s plea for help in Spanish didn’t come to light until a New York Post story published about a month after her murder.

“It could have been avoided,” said Roger Asmar, a lawyer hired by García’s family.

Deisy García’s murder underscored a tragic reality faced by many immigrant women who are victims of domestic violence: Being able to communicate effectively with law enforcement officials can be a matter of life or death.

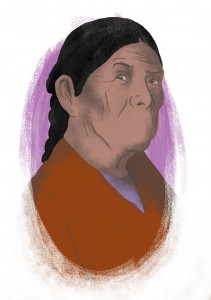

“It’s negligence – and it’s a lack of responsibility by police,” said García’s mother, Luzmina Alvarado. “They are supposed to do their job.”

Luzmina Alvarado, Deisy García’s mother, in her apartment in Jamaica. (PHOTO: María Sánchez Díez)

A CITY’S SHIFTING ACCENT

When asked about Deisy García’s slaying, the NYPD noted that the department boasts one of the best translation services in the country. Some 37 percent of employees have some level of proficiency in a language other than English, according to NYPD figures.

But the murder and interviews with other Spanish-speaking domestic violence victims in the city suggest the system is still far from perfect.

The women say they are consumed by fear – of their abuser, of authority, of not being heard, of being rejected by their own families for exposing private marital strife. Above all, they say they are afraid of deportation and of losing their children.

“It’s very scary, because you see a police car arriving and you never know how things are going to turn out,” said Ángela, a 27-year-old undocumented immigrant from Mexico. Like other women interviewed for this story, she requested that her real name not be used.

Ángela said she called police twice in 2012 to report beatings by her now-estranged husband.

On one occasion, Ángela said, an officer told her: “You Hispanics, you all do the same: Today you want him arrested and tomorrow you’ll want him out.”

I didn’t think that domestic violence was happening to me, because I thought that domestic violence meant to be hit or threatened. The violence eventually became physical, but I later learned that violence also can be emotional, sexual, economic.

The part that struck me the most was the emotional, the sexual. Sometimes he would force me, and he would say, “You’re my wife, and this is your job.” Sometimes I did not want to and I suffered a lot of vaginal infections. I went to the doctor and I was told it was natural, and probably caused because I did not lubricate. But it was rape.

He left to work in Minnesota for three months. My rent was $700, and I had to gather $1,000 (for expenses). And I said: “Of course I can. I’m going to do it.” I babysat a girl and I got paid $115. I told my sister: Keep $100 and do not give the money to me unless I have an emergency. With the $15 that I had left, I bought jelly, plastic glasses and plastic wrap (to repackage the jelly for resale). I went to a school to sell jelly. With the $15, I made $30. I bought juices and fruits. I walked in Queens, on Junction Boulevard, selling mangoes, watermelon, melon, water, sodas and juices. I was pregnant. I thought, “Even if I am pregnant, I am able to make money.” I kept working. Within three days, I collected $800. And I decided to leave.

Now I’m with my son. We are not doing great, but we are doing well. No one shouts at us, no one mistreats us. Sometimes I cry with joy because I once lived from room to room, a month in one apartment, another in the next one. I had to go live a shelter, from Dec. 17, 2013 until Feb. 23, 2015. During that time, it was very difficult. Today I have an apartment in West Harlem. My son has his own bedroom.

Now I have working on my own for two years. I sell Herbalife products. I am very grateful to the people who helped me. I learned that we are never alone. My goal is to help at least one more woman.

New York has more people than ever – up to 1.8 million or more than 20 percent of the city’s population – whose first language isn’t English, according U.S. Census figures. Many of these people speak English. But others scrape by with minimal proficiency.

In recent decades, the NYPD has worked to catch up with New York’s shifting demographics and, like the rest of the city, has become increasingly diverse – thanks in part to a 1978 federal court decision that forced the hires of more black and Hispanic officers.

About one-quarter of the force is Hispanic, but it’s not clear how many of those officers are fluent in Spanish.

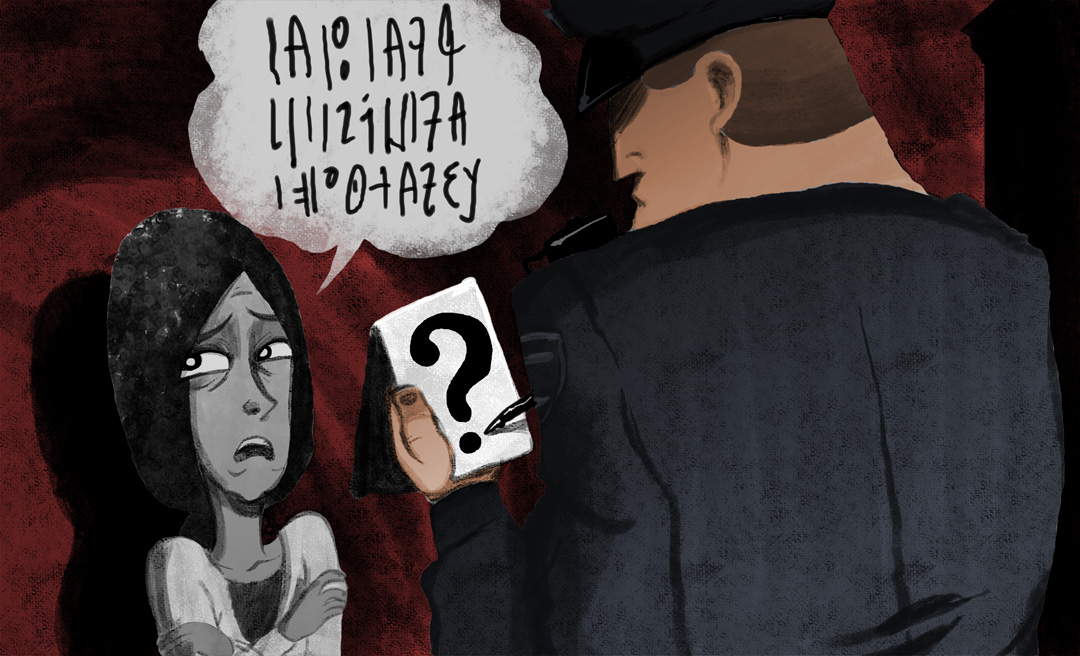

Illustration by Javier Güelfi

The NYPD says the department has more officers and other workers who speak a foreign language than any police agency in the country. Overall, some 19,000 NYPD employees speak at least one of 75 foreign languages, from Albanian to Yiddish. The department also has 1,200 certified interpreters among its ranks.

In 2008, then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration expanded the city’s language access policy. The NYPD Language Access Plan, published in 2009, requires officers who respond to a scene where interpretation services are needed to find and provide them.

This assistance could come in the form of other NYPD employees or via the Language Line, a telephonic interpreting service contracted by the city. Officers have access to a dual-handset phone that can get a third-party translator in an instant, said Sgt. Carlos Nieves, an NYPD spokesman.

In a city of many languages, crime also has become polyglot. In September 2015, about 2.5 percent of calls to 911 required interpretation services, while the percentage for October was 2.7. In 2010, the most recent full year for which detailed statistics were publicly available, the Language Line processed 112,587 calls in 85 different languages. Spanish represented an overwhelming majority of those calls: 89 percent, followed by Chinese (6 percent) and Russian (2 percent).

However, advocates point out, there’s a huge discrepancy between the number of 911 calls that need an interpreter and the actual number of requests for such services made by police officers in the field. For example, in November 2014, 911 operators processed about 7,000 calls that required an outside interpreter, but the police only used that service 32 times during the same period, WNYC reported.

Some advocates contend that the NYPD’s record on providing interpretation services is spotty and that officers don’t always use the resources that are available to them.

“What we see a lot is that, if a person speaks four words of English, she is told that she doesn’t need an interpreter,” said Carmen Maria Rey, a lawyer and deputy director of immigration at Sanctuary for Families, an advocacy group that works with domestic violence survivors.

Rey said that some police officers don’t fully understand that people who can speak minimal English are often unable to convey complex situations.

“The other difficulty we see is that the police officers don’t speak the [foreign] language well enough to communicate thoroughly,” she said. “They only can communicate at a very basic level. That is not enough.”

In 2010, the Department of Justice stated the department’s language access policy was “not fully in compliance” with the Civil Rights Act, which forbids discrimination based on nationality. A Justice Department follow-up review two years later found the NYPD to be in compliance.

The NYPD notes there is no federal law or regulation that bars officers from using foreign language speakers who are not certified. “Beyond that, there is not a single documented case in which the use of a non-certified employee failed to translate properly,” according to the department’s website.

But not every failure is documented, domestic violence victims and their advocates contend.

FIGHTING TO BE HEARD

In May 2013, seven months before Deisy García’s murder, Legal Services sued the city in Brooklyn Federal Court on behalf of five Hispanic women – four of them survivors of domestic violence. All of five had been denied interpretation services that the NYPD is mandated to provide, the suit charged. The lawsuit [full document] also denounced “routine discrimination” against immigrant New Yorkers who seek police assistance.

“NYPD personnel not only fail to provide language services, but on many occasions actively mock and humiliate LEP (Limited English Proficiency) individuals who request such services,” said the complaint, inherited by the De Blasio Administration and still unresolved.

The lawsuit details several examples, including the case of Arlet Macareno, a then-26-year-old Mexican immigrant who says she called police after her husband pushed her down the stairs in August 2012. The officers who showed up at her Staten Island home ignored her request for an interpreter, talking instead to Macareno’s 22-year-old niece, according to court papers.

When Macareno insisted on an interpreter, one of the officers told her, in Spanish, “Cállate la boca” (“Shut your mouth”) and ended up arresting her. On the drive to the precinct, the officers made jokes about the Mexican national soccer team, according to the lawsuit.

Macareno, who was barefoot when she was arrested, said she spent the night at the precinct with no shoes.

When plaintiff Wendy García asked for an interpreter after her husband slammed a door on her and pulled her hair in Queens in 2012, police told her: “This is America, you have to speak English,” according to court papers.

The cases cited in the suit echo accounts by women interviewed for this story, among them Aida, a 42-year-old Mexican immigrant who called the police four times over the course of one year to report abuse by her husband.

“I understand that we have to speak in English, but not all of us know how to,” said the mother of three, who is trying to learn English.

Christine Clarke, an attorney at Legal Services NYC, said that 911 operators are often helpful with providing language assistance, but added that foreign speaking crime victims’ interactions with police can be less predictable.

“For some of the people in the lawsuit, the police just wouldn’t talk to the crime victim at all because they didn’t speak English,” said Clarke. “If her abuser spoke English, they would speak to the abuser but not to her, and sometimes that means they would arrest her even though she was the one who was beaten up.”

Rey said that some victims end up with criminal records, which can hurt their chances of staying in the country. “What we see often is that the police arrest [the couple], because [the officers] cannot communicate,” she said, “and they don’t know how to make a determination of who they should believe.”

The NYPD language access plan includes guidelines for officers who encounter domestic violence situations. Officers are advised not to use family members – especially children – to interpret “due to fear of arrest of a family member or other personal biases,” unless there is no other alternative. The guidebook also recommends that victims be interviewed privately.

“Using an alleged offender to interpret may increase the risk of purposeful misinterpretation and gives him or her control of the situation,” the guidebook states.

Aida said the third time she called the cops, her husband started insulting her and threatening her in Spanish in front of the two officers.

“He was calling me a dog and other ugly things,” Aida said. “Then the officer asked him what he was saying to me and he answered that he was telling me that everything was going to be fine.”

I sell tamales on the street. I do that from Monday through Thursday. I have many customers and everyone tells me, “You never seem to have problems.” But then I go home, I pick up my son, I arrive about ten o’clock at night, I give him a bath (he has always already eaten). I put myself to sleep and say, “What a life.”

I’m going through a very difficult situation emotionally, because I have no family here. I am alone with my two older children and the younger boy. I have no one. All my family here in the USA is in California. And there are times that I do not know what to do… I would like to have a coffee with my sister, so if I’m feeling bad she would say to me, “I’m with you.” Or just to be able to tell her, “You know what? Let’s take a walk to the park, you and me.”

I cannot see anything violent because it makes me hysterical. It gives me great anxiety. Before, I was a fan of watching the news…

When I was little, my aunt from California gave me pajamas with Disney characters on them and I said, “Oh, I’ll go there someday.” It’s been my dream, since I was a chamaquita (a little girl), to go to Disneyland. Maybe it’s ridiculous, because I am a middle-aged woman. If God wants me to, next summer, I will take my son to Buffalo, because I also have always wanted to see Niagara Falls.

“I said to myself: ‘If I am the one who is being hurt, if I’m the one who needs help, why do they talk to him?’”

HELPING WOMEN TO SPEAK UP

Advocates believe that the most effective way to push the NYPD and other city agencies to fulfill their Language Access Plans is to urge more women to demand their rights.

The Violence Intervention Program, an organization that helps Hispanic domestic violence victims, gives women a piece of paper stating their right to access an interpreter. The women are encouraged to carry the paper with them show it to authorities when needed, said Lorena Kourousias, program coordinator of the organization.

“What we need is people to know that they have the right to an interpreter and they can demand an interpreter,” said Rey. “Part of the responsibility is ours to complain when we are not offered an interpreter.”

Some domestic violence victims and their supporters, though, are learning the value of speaking out. Hundreds of women wearing white wedding dresses participated in the Sept. 26 annual Brides March through Washington Heights. The yearly demonstrations mark the 2001 slaying of Gladys Ricart, a Dominican woman murdered by a former boyfriend on the day she was to marry another man.

Advocates they see the Legal Service lawsuit as an additional step toward progress. Clarke said her group hopes to drive change in the enforcement of the language access policies.

“Litigation can be a way that sort of helps move that up a little faster and also could help uncover problems that nobody wants to look at,” she said.

SEEKING A WAY OUT

Abusive husbands yield weapons beyond physical violence. They can isolate their wives, forbidding them, in some cases, to work or socialize.

Many immigrant domestic abuse victims are poor and uneducated, with no network of support amid cultural taboos about reporting their husbands to law enforcement authorities.

“Abusers consistently threaten them, saying that they will get deported if they go to the police,” said Kourousias.

That matched the experience of Rosa, a 56-year-old mother from Provincia del Cañar in Ecuador.

“He [my husband] always threatened to send me to the police and have me deported, if I tried to get a divorce,” she said. “And I didn’t know that I had access to help or anything, because I was always working, and I was desperate. I was very afraid that something would happen to my children.”

In Ecuador, I made crafts from paja toquilla (an Ecuadorian kind of straw) as a living. I did dolls, hats. I am from the country, I had chickens. I like New York, that’s why I haven’t left. Since I arrived, I have worked at everything: in factories, cleaning houses…

I rented space in my house because I could not afford the mortgage by myself. I rented a room to a man who said he had fallen in love with me. At first I did not believe him. I thought he just wanted to sleep with me. But as the time passed, he was always waiting for me, helping me clean. He seemed to love my children so much. We got married in 2007. And then I began to really know him.

He told me horrible things I had never heard and never want to hear: That a woman has to give pleasure to men. He threw things at me. Once he grabbed (my neck) and said, “You’re useless.” He would tell me that I had never learned anything because I’m just a peasant. He always threatened to report us to the police, when I threatened to get a divorce. He said he was going to get me deported.

I did not know that I could get help. I was always working. I was desperate. I was very afraid that something would happen to my children.

He told me he was going to help with rent, but then he stopped. He wanted to live for free. I didn’t pay a few months of mortgage and I lost the house. The house was registered in my brother’s name because I am undocumented.

My children and my brother were upset with me. They resented me. I was alone.

I always try to forget… I go out somewhere, I talk to someone to distract me. But if I stay home, I spend my time crying. Now I’m living with my brother, but I’m paying him rent. It’s not like I would like it to be. Before, I had a sewing machine, and I was able to do work in the house. Now I have no space. And that’s all I can say.

Many undocumented women who are victims of domestic violence don’t realize they are eligible for a U Visa, a special permit that the Department of State issues for immigrants who have been crime victims. Last year, 10,000 of these visas were issued, mostly to victims of domestic violence, sexual assault and human trafficking. But it sometimes can be difficult for women to convince authorities that they’re victims of serious crimes.

“If, for example, a person was choked, but the police record says that she was pulled by her hair and the officer writes that the crime was just harassment, that’s not enough for us to try to make a case for the U Visa,” Rey said.

Claudia, a 34-year-old immigrant from Mexico, got her U Visa after surviving the hell of domestic violence. Before her husband was deported, he threatened to kill her parents back in their town in Mexico. With the visa came a feeling of relief, but the shadow of that menace remains.

“I often think: What if he does something someday?” she said.

I was 17 when I married him. I had problems almost since I met him, but I never wanted to tell anyone what was going on. One day, three years ago, we had an argument. That day, he hit me so hard I had to go to the hospital. He hit me hard and dragged me. Then he hit me on the forehead, until I started bleeding. My girl, the oldest, was 12. She called the police because she was scared.

Then he left home for a long time. I did not hear from him for years. He returned and attacked me again last year. He attacked me on the street. He grabbed my hair and started to drag me down the street.

I thought he was going to kill me there. But he released me and the police grabbed him. At the precinct, he said he was going to kill my parents. I made a report.

I started thinking about my parents and thought, “Oh, and if he kills my parents, what will I do? It will be my fault.” I told the police I did not want to press charges against him, because I was afraid for my parents. We come from a culture that speaks Mixtec [one of the main indigenous languages existing in Mexico], and do not understand things well.

The authorities later deported him. When I got my U visa (a type of visa for which undocumented crime victims are eligible), I felt good. But suddenly, I also felt bad because I often think, “What if he does something (to my family) someday?” And I don’t know, it must be because I lived with so many years of violence and I know it is stupid to say this, but it feels like something is missing. But it is not good.

My goal is to overcome, to keep on studying. I lived with great fear. I study English in the Bronx, in the church. I finished school in Mexico, but I want to get a high school diploma. I would like to defend people.

After everything that happened to me, I thought I was not going to make it. But I realized that when I put effort into things, I do well. I take care of my children and they are doing well. I am a home attendant, and in the summer I sell fruit on the street. I would say that nothing can stop me. I got my driver’s license, I bought my car… I can do things in life.

To be eligible for a U Visa, a crime victim must cooperate with law enforcement officials. But many undocumented immigrants try to avoid interactions with police at all costs.

“I was terrified of walking near the precinct, I thought the police were bad,” said Aida. “He [my husband] told me I was illegal and I was going to get grabbed.”

For some undocumented immigrants, the fear of deportation eased after President Obama’s decision in November 2014 decision to shut the federal Secure Communities program, which allowed local authorities to share fingerprints of jailed immigrants with the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

New York is among the cities that didn’t follow the program, which started in 2008. That decision might have helped Mejía Ramos. In July 2010, he was stopped for a traffic violation and immigration officers started a deportation process. However, in April 2013, his case was closed because it didn’t match the federal guidelines to focus only on serious crimes, an immigration official told The New York Times.

Nine months later, Mejía Ramos would murder his wife and daughters.

The exclusive from the New York Post

A FAMILY BATTLES GRIEF

It’s a sunny early December Sunday afternoon in Queens. As she does every week, Luzmina Alvarado attends services at the Iglesia Naciones Unidas en Cristo church in Jamaica.

She said that going to the Sutphin Boulevard church eases her grief. So does looking at the pictures of her daughter and granddaughters on the walls of the modest apartment Alvarado shares with her three sons.

She points to the last picture her daughter took: A smiling Deisy García, sitting in a chair in front of a Christmas tree. In another photo snapped that day, García, Yoselin and Daniela pose in front of the tree, wearing matching red dresses.

As the second Christmas without her daughter and granddaughters approaches, 37-year-old Alvarado says she still doesn’t feel like celebrating the holidays.

This year, at least, she set up a small tree with white lights. Last year, she spent Christmas weeping.

She’s not the only one. Her sister, Sara Alvarado and brother-in-law Romeo Chuc, who discovered the bodies, are still haunted by the memory. Sara Alvarado went to therapy for seven months until she ran out of money. She doesn’t spend much time these days with her sister – it’s too painful for both of them.

Romeo Chuc and Sara Alvarado, Deisy García’s uncle and aunt in their new Jamaica apartment. (PHOTO: María Sánchez Díez)

After García’s death, NYPD officers were instructed to translate every non-English domestic violence report.

“These reports are brought to the precinct and it’s the responsibility of the officer or official there to translate them,” said Nieves, the NYPD spokesman. “In the past, there were instances in which [the reports] were not translated and a tragedy happened. But we are taking action so it doesn’t happen again.”

Nieves said the department is testing a Microsoft translation app that recognizes the language a person is speaking. The NYPD estimates that all 35,000 officers will have a Nokia phone with this app by April 2016, Nieves said.

On Nov. 21, 2015, just in time for the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, Gov. Cuomo signed a law, prompted by her slaying, that requires police statewide to rapidly translate crime reports to English. Before that, there was not a protocol outside the city.

“It seemed to me as something that could be easily avoidable,” said Senator Brad Hoylman, precursor of this bill. He learned about García’s case on the press. “We hope this is a small comfort to her friends and family.”

The institutional response has not arrived to Jamaica, though. Alvarado did not know that her daughter’s death had inspired a bill and she said that no one from the NYPD or the city has offered to help her. She said she understands that her daughter wasn’t American, but notes that Yoselin and Daniela were born in New York.

“They had rights, but it seems as if they were worth less than a little dog,” she said.

Asked if she wants an apology, Alvarado replied: “I don’t care anymore. My daughter is already dead.”

Alvarado, who works cleaning houses in the city, spends much of her time thinking about what was and what could have been. She started working in Guatemala City as a babysitter at age 12. She married at 14 and had Deisy less than a year later. She said she worked hard to bring Deisy and her three younger brothers to the United States.

“I wanted a different future for her,” she said.