By Clemente Álvarez

At times, the work of research scientist Mauricio Hoyos requires him to put on his neoprene wetsuit and jump in the water. Nothing special, if it weren’t for the fact that it’s his job to study great white sharks. Surprisingly, he’s not in the habit of using a cage. Nor does he protect himself with any kind of steel mesh attire. “The pressure from a shark bite is 1.8 tons per square centimeter, so it wouldn’t do me any good,” states the Mexican marine scientist who has been tagging sharks off Guadalupe Island, a small nature paradise 149 statute miles off the coast of the Baja California peninsula. He wears only his wetsuit, and an electric pulse device meant to ward off attacks, which he has never activated.

“The great white shark is the perfect predator. It has the best sense of smell of all other sharks, sees very well, and in color, and even has an over-developed sense of hearing that it uses to detect low frequency vibrations coming from the erratic movements of dying fish,” states Hoyos, who is also director of the NGO Pelagios-Kakunjá.

“However, it also has the blister-like ampullae of Lorenzini, consisting of a series of pores on its nose which it uses to detect water temperature or electromagnetic fields. This is used to detect prey, even if such prey lies hidden underneath the sand,” says Hoyos. (For more information about this and other sharks, click on the plus sign).

Of the more than 500 shark species in the world, the great white is the most feared. Hoyos tags them to gather scientific information, but also to save them from other, much more lethal predators: humans.

“At first it is very breathtaking, but when you join them underwater and see them up close, you realize they’re not monsters.” There are, for example, some with which he is now accustomed to swimming, such as Lucy, the female with the short tail. And others are very hard to see: such as Deep Blue, one of the largest great white sharks ever recorded. A few weeks ago, he found an old video of this giant of the depths on his computer and posted it on his Facebook page.

“This is the largest shark ever seen from the cages at Guadalupe Island…Deep Blue!!!” wrote the researcher, who had shown no fear of touching this particular shark while he remained outside the cage, as shown in the video. It took no time in becoming viral. “As with any other animal, the risk is being too trustful, but they are not wanton killers.”

While the exceptional Deep Blue has much showbiz appeal that surrounds this species today, its size is an interesting reference for refuting a mistaken image of these animals that still persists. There are no reliable measurements of the hulk that appears in the images, even though Hoyos states that it was larger than his 21 foot boat. All things considered, it falls within a reasonable range.

According to the researcher, the largest great white shark for which there are reliable measurements is a female caught to the north of Cuba, 19 feet (6 meters) in length. Nevertheless, if we now switch over to the movie screen, the robot in Spielberg’s film Jaws measured more than 32 feet (10 meters), almost double. Unfortunately, this is not the only exaggeration used by that 40-year-old film in its attempt to make sharks appear more fearsome.

What then is happening, with attacks occurring in North Carolina this summer, some of them very serious and involving amputations? Of the 72 attacks registered last year throughout the world, 50 took place in the United States, and of these, most were in Florida, especially in Volusia County (20), and more specifically at New Smyrna Beach (here you can watch a video recorded a few weeks ago about the world’s capital of shark attacks).

As explained by George H. Burgess, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research, most of these incidents are bites by small sharks measuring some six feet and are very rare in proportion to the number of people who get in the water.

“Occasionally, along Florida’s beaches you may find other larger sharks, such as the bull shark or the tiger shark, which hunt large prey such as other sharks, rays and sea turtles,” explains the researcher, adding that now is the precise time when turtles breed. As has happened in North Carolina, these attacks occur, but they are even more rare.

Furthermore, these incidents are almost always by accident. “If sharks wanted to eat humans there would be thousands and thousands of attacks every year. But generally speaking, sharks swim away when they detect people because we are not part of their diet, as we are not marine animals. Most of the time they swim away, since they are not interested in us. Of course they sometimes make mistakes.”

Statistically speaking, there are many other things to worry about first at a beach. “I don’t think we need to be afraid of sharks,” comments Burgess, who on the other hand believes we have to respect them. “Whenever we go into the ocean, whether it be in North Carolina, Florida, or wherever, we’re not getting into a hotel pool.”

The truth is that the ones being brutally hunted down, in a premeditated way, are the sharks themselves. Estimates such as those made in 2012 by research scientist Boris Worm, of Dalhousie University (Halifax, Canada), suggest that human beings kill some 100 million sharks each year. In other words, more than 11,000 are killed each hour. “Going back some years, sharks have been the most endangered species of fish on the planet,” points out Georgina Saad, director of the WWF Marine Species Program in Mexico, who explains how, in great measure, this is the fault of a soup.

Among the species having the worst luck are the tranquil hammerhead sharks, the animal with which divers began to lose their fear of swimming among sharks. As explained by Director Saad, the hammerhead shark has been one of the most sought-after for the sake of cutting off its fins, which may draw 50 dollars per pound on the Asian market.

That is what is called ‘shark-finning’ for making shark fin soup. The rest of the flesh is often thrown away, or sold at a low price. “What’s the value of an animal that takes so many years to grow, and to reproduce, and that plays a key role in the ecosystems?” Saad asks herself.

The whale shark is the biggest fish in the world. This impressive animal can weigh as much as 20 tons and lives to be as old as 70 years. Highly docile and possessing miniscule teeth, it is not as frightening as other sharks, which has helped to turn it into an attraction in tropical waters. In places such as the United States or Mexico, it is not fished and it contributes to generating revenue through tourism.

Nevertheless, as Saad laments, in other Asian countries, such as the Philippines, they also cut off its fins. “Shark-finning affects all sharks,” she says indignantly. “I would simply prohibit shark soup. I would say, ladies and gentlemen, from now you may not sell shark soup, and any restaurant that sells it will be fined. And I would subsequently pressure countries that continue to allow it.”

Even though the biggest problem is in Asia, there are also eateries elsewhere serving it. And fishermen who cut shark fins may be anywhere. Recently, the police in Ecuador seized 200,000 shark fins at the port city of Manta. The shipment was about to be sent to Asia illegally and it is estimated that this had involved the death of at least 50,000 sharks.

When Saad goes food shopping, she is very alert as to what there is at the fish market: “First, I choose the person from whom I will buy the fish. This is very important. And, secondly, I know how to distinguish between what comes from a normal fish and what is shark meat. Shark meat is very white and its fibers are not as small.” She knows how to distinguish between a commercial species and one that is not supposed to be there.

Of course it is much more complicated for consumers. “In Mexican markets we have even seen white shark meat being sold. Sometimes it is sold as if it were tuna, yet leaving on the shark’s fin, which is very characteristic.” Unfortunately, at other times it is much more difficult to know what species it is and where it was caught. This may have to do with what reaches the fish market, as well as the contents of some pills containing shark cartilage.

The most surprising thing about sharks is how little we still know about them. In part this has to do with how difficult it is to study them. In the case of Mauricio Hoyos, the hard part is no longer getting in the water with the sharks, nor taking them out of the water to tag them, but simply having access to the remoteness of Guadalupe Island.

For him, the trip is worthwhile only if he goes to spend three or four months. “We know very little about them, we don’t know where they reproduce, or where they keep their offspring,” explains the director of Pelagios-Kakunjá, who considers this information to be the key to protecting the areas that are the most sensitive for their reproduction.

Today’s availability of different kinds of tags, such as those used by Hoyos, and the ability to follow shark movements by satellite is revolutionizing their study. As research work began using these new technologies, cases were discovered such as that of female great white shark P12, documented in a 2005 article in Science.

The specimen, 12 feet long, astonished scientists as they learned it had travelled 6,807 statute miles from South Africa to Australia, only to reappear a few months later back in South Africa. This shark had completed an incredible round-trip migration of more than 13,000 miles. It then became evident that there is yet much to be discovered about sharks. Since then, studies have followed that show the great mobility of these animals.

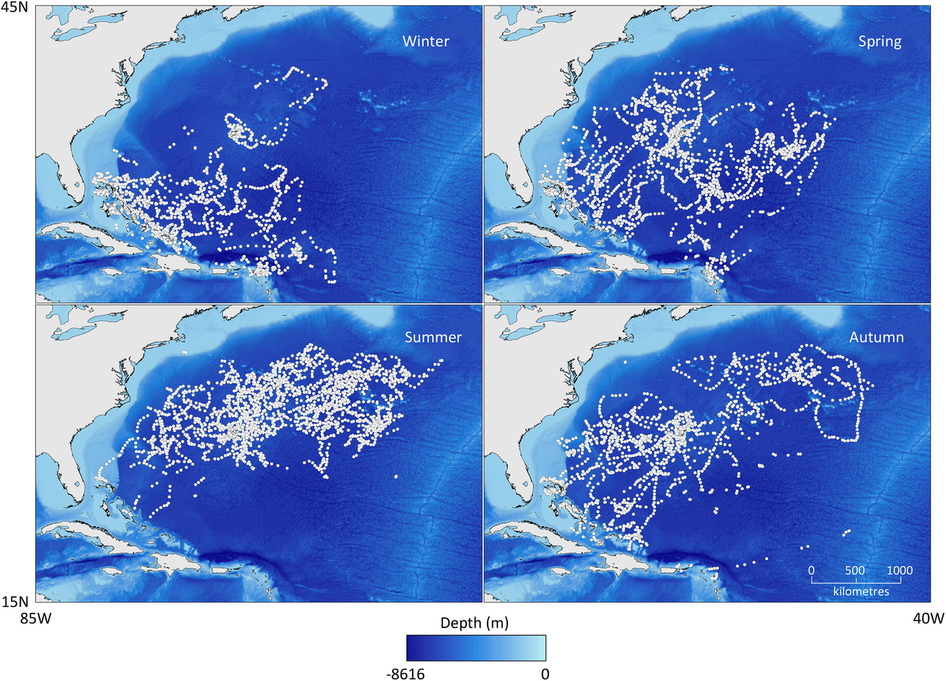

One of the most complete studies using tags has been recently published by James S.E. Lea of the Guy Harvey Research Institute in Florida, and it reveals how tiger sharks repeat annual migratory patterns spanning 4,660 miles between the coral reefs of the Caribbean in winter and the more open waters further north in the Atlantic Ocean in summer.

These migrations are more like those of birds, reptiles or mammals than those of fish. All of this research shows sharks are incredible animals, but are also hard to protect. “Sharks are extremely mobile and don’t respect human boundaries,” explains Hoyos. “It is useless to protect them in the United States or Mexico when they are hunted down once they go further south.”

It makes no sense to exterminate these incredible creatures for the sake of a bowl of soup, nor does it make any sense to say we don’t care because they scare us. Even though the United States is the place with the most shark attacks in the world, one is much more likely to die from being struck by lightning (26 deaths in 2014, six of which were in Florida) than from a shark bite (zero U.S. deaths in 2014, and only three in the rest of the world: two in Australia and one in South Africa).