2California’s bad dream

By Clemente Álvarez y Nacho Corbella

If you close your eyes, you can almost imagine yourself by the sea. But you have to try very hard to pretend you hear the relaxing sway of the waves. Fshhh…, fshhh…, fshhh… It would be perfect if you could just forget about the smell. There is also that disturbing creaking sound the ground makes as you walk. And the worst comes as you open your eyes again to have a look.

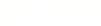

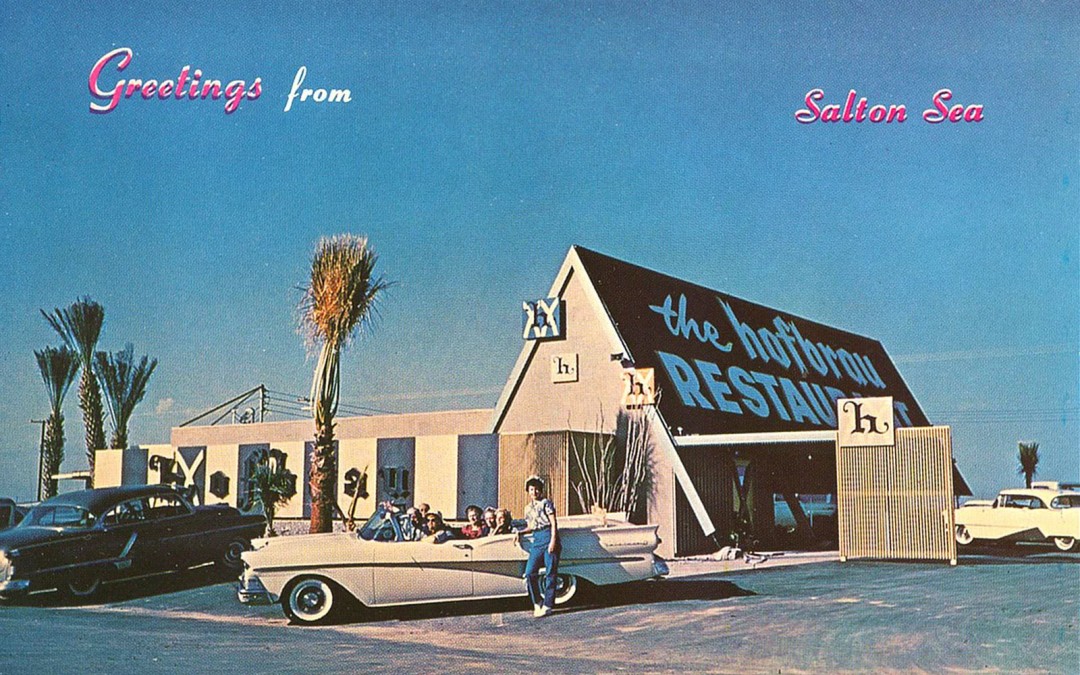

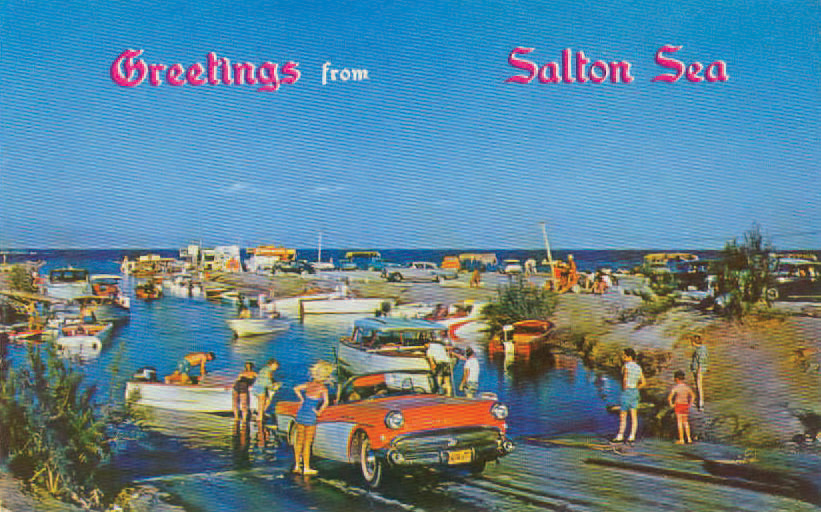

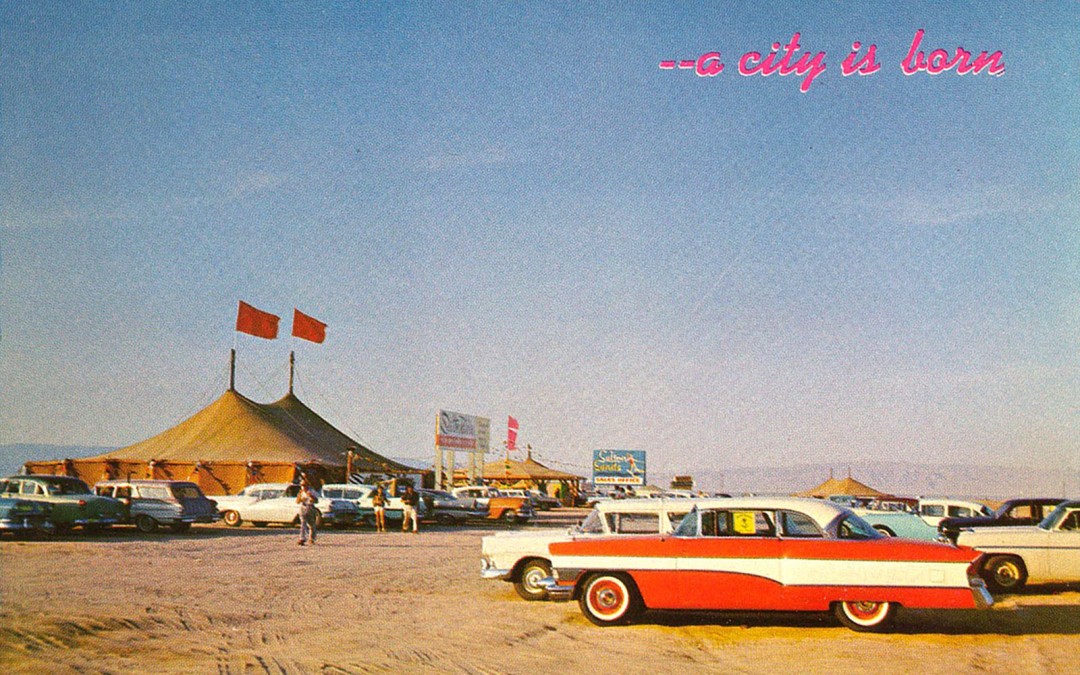

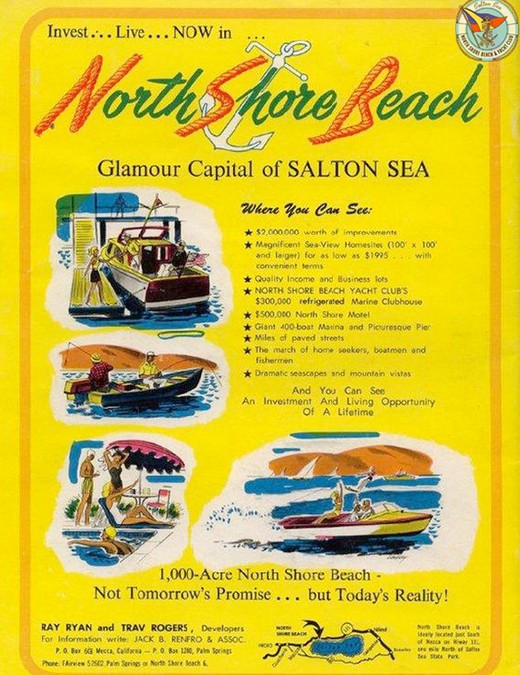

After going through Mexico and Arizona, our journey upriver now reaches California. We move away from the river a bit so as to stop along the Salton Sea, a lake large enough to be called a sea, where you can see how water can turn dreams into a nightmare. Once a glamorous beach in the middle of the California desert, it is a sick coastline today. This place, where famous people such as Jerry Lewis and Frank Sinatra once had their pictures taken, now looks like a scene hatched in the mind of Alfred Hitchcock: a shore where you tread not on sand but on the empty carcasses of crustaceans and dead fish, amidst the putrid odor and the flies, many flies.

José L. Ángel brings out a pointer and shows us a large blue blot on the map he has taken out of the car. “The Salton Sea is the largest lake in California, six miles wide and some 60 miles in length, and it was created by accident,” he says. Mr. Ángel maintains an office in Palm Desert as an assistant executive officer of the Colorado River Basin Regional Water Quality Control Board. He knows this spot on the map as few others do, but also the many paradoxes connected with the use of water in California. “We have the largest lake in the entire state in the place that gets the least amount of precipitation; it doesn’t seem logical,” he comments while surrounded by the arid lands. “Perhaps this gives us some clues as to why we’re going to have to make adjustments in the way we use the water.”

Even though it is separated from the Colorado River, the Salton Sea is at the same time part of it. The lake was formed between 1905 and 1907 when engineers made a big blunder as they built a canal near the border with Mexico. The result was the diversion of the Colorado and the floods that created a catastrophe, mostly in Mexicali. For two entire years the river’s course flowed into the flat area known today as the Salton Sea—until the normal course was reestablished. After the disaster was over, the outcome had its good side. The fresh water from the melting snows of the Rocky Mountains had transformed part of the California desert into a vacation wonderland. They built resorts, entire neighborhoods with gardens and palm trees, and sailing clubs—with celebrities competing in powerboat races—until everything began to rot. The water became more and more saline. For years this was not seen as a problem, but then the dead fish began to appear.

The shores of this huge lake are now filled with abandoned houses. A metal barrier blocks the way. There is a murky building with broken windows and an open door whose threshold would be better not to cross. As in horror movies, it turns out to be irresistible. Inside, the darkened hallways weave together stories of broken dreams. A doorway leads to the Desert Shores yacht club lounge. There you get the impression that the music is about to begin and the waiters are ready to serve at tables where one sees and hears the laughter of the dinner guests. But everything is empty, plagued by sadness. Only some graffiti remain on the walls along with the remnants of a newspaper dating back more than 20 years. Looking through the broken windowpanes, it seems incredible that people keep living around here. But right next door there is a trailer park and houses where people live. And Hispanics are a majority here.

As Mr. Ángel continues to explain, making use of his pointer, before the great flood of 1905 a lake known as Cahuilla Lake had emerged several times, only to then disappear. When the link to the Colorado was blocked off, the Salton Sea should have dried up again. But this time that did not happen because of a key change in the use of water in California. At the start of the 20th century, the development of agriculture had already begun in the Imperial Valley. 70% of California’s allotment of Colorado River water ends up in these fields. And nearly a third of that enormous volume dedicated to irrigation becomes wastewater filtration into the Salton Sea. Yes, the rest of the water used for agriculture in the deserts of Southern California is enough to fill a sea, in this case the largest lake in the state.

“The largest and the filthiest one,” laughs Jesús Sánchez in a dark living room while we enter one of the houses in Desert Shores that seems inhabited. He is one of the many Latinos who came to the Salton Sea, attracted by the house prices that were dropping as those who could were fleeing. With the curtains drawn and the air conditioning freshness, the modest house belonging to this family of six is even cozy. “For us this house is a luxury, you don’t know what it’s like having to live with small children in a trailer,” explains this Mexican farmworker, surrounded by his wife and children. When they purchased the home, they were given assurances that there was a plan to clean up the lake, but that wasn’t true. According to Mr. Sánchez, when the temperature rises, the bad smell reaches this far. “It smells like something rotten,” he says. Despite everything, this is their home, even though they cannot go outdoors. “There are lots of flies. So you have to stay indoors just as we are at present. Locked up here, that’s how we spend our time right now during this season.”

The irrigation water from the Colorado has provided jobs for these Latinos and the polluted Colorado River water has trapped them in their houses. As Mr. Ángel explains it, the salinity is a result of the irrigation, combined with the high temperatures. As an approximation, the amount of salt coming from the water draining out of the fields of the Imperial Valley, together with lesser amounts from Coachella and Mexicali, is equivalent to a mile-long train loaded with salt that ends up in the Salton Sea every year. This causes the water to be 30% saltier than the ocean. “So much salinity is toxic for many species, but this landlocked lake further accumulates other pollutants, nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphate. We have had millions of fish die in just one day,” says Mr. Ángel, who is also in charge of water quality. “Then there’s the murkiness and the bad smell. I’d rather not go swimming in there.”

A child sinks into the water. He has lost the water tube to which he was holding and does not know how to swim. He desperately tries to come up for air, but the current draws him in again. When he was only 11 years old, José L. Ángel almost drowned in the Colorado River, on the Mexican side. Some youngsters rescued him, down by the bridge at San Luis de Río Colorado, at the same spot where today there is only dry sand. “It is sad to see how all this has changed. For me, the Colorado is a river that creates miracles. There are millions and millions of people who benefit from its water, and not just in California. It turns out to be strategic and represents life for the deserts,” Mr. Ángel points out. “But it’s an endangered river and the forecast isn’t pretty.”

In the Salton Sea neighborhoods, it’s disturbing to see houses with boarded up windows and dead palm trees in the yards. But just as disconcerting are those houses in perfect shape right next door with colorful potted flowers and recently mowed lawns. The Sánchez family does not know their neighbors, even though they know there are many other Hispanics, who just like them, work in agriculture. “We work during the grape harvest, we plant chili, green beans, lemons, oranges, all sorts of citrus,” comments Mr. Sánchez. “We spend a lot of time out on the fields. It’s tough. When we return we want to rest, but then we are greeted by this smell.”

It is difficult to ignore the stench. Although there is another fear that keeps him restless: drought. “They say they will reduce the water. We are concerned about all this because almost all Latinos work in the field. Without irrigation, ranchers will stop growing. And what are we going to do then? We don’t know to do anything else.”

One of the places that have no water shortage, even when there is drought, is the nearby Imperial Valley, the source of the water that drains into the lake. With 180,000 inhabitants, this place uses up 70% of the Colorado River water allocated by rights to California. In other words, more than double the amount of water available to nearly 20 million other people in Southern California, or 10 times more than for all of Nevada. And as with the Salton Sea, most of the people (some 80%) are Latino farmworkers. “We can’t blame Hispanics, as we’re the ones who harvest the crops, but we’re not necessarily the owners of these lands,” Mr. Ángel emphasizes. When there isn’t enough water for everyone in this part of the basin, he explains, priority is given to those who have held water rights for the longest time. Should the drought become worse, the last to have their water supply cut off would be the farmers around Blythe. Those with longer standing rights are the Quechan Indians of Yuma or the families who own the land in the Imperial Valley.

“The problem in California is that we want to use laws that were enacted hundreds of years ago,” stresses Mr. Ángel, who states that the water over which there are so many disputes is of a greater quantity than that of the river itself. “Whisky is for drinking and water is for quarrelling,” he summarizes with a smile. The Regional Water Quality Control Board offices, where he works, are in Palm Desert, a city next to the desert, but covered with green lawns. There are nearly 30 golf courses and some 48,000 people live here. And in this case the proportion of Latinos drops significantly (20%), even though many of them continue to play a key role: that of gardeners. When we move along De Anza Way, two of them, the Barajas brothers, Alex and Antonio, are busy performing a task that—in these exclusive neighborhoods—could easily be accompanied by the squeaking violins, violas and cellos of the soundtrack of the movie Psycho… They’re pulling up lawn, as part of the water conservation measures resulting from the drought. “If we don’t cut back on the watering, we will be fined,” they explain without interrupting the lawn removal process.

California’s prolonged drought has demonstrated that water can put even some of the richest places on earth in a bind. And not just for esthetic reasons. With water consumption in some cities in this part of Southern California exceeding 350 gallons (1,324 liters) per person per day, the gardens have become a prioritized issue for reducing consumption. In fact, many houses in Palm Desert have already replaced their lawns with cacti. Nevertheless, the savings that can be obtained in urban areas are very small in comparison with agricultural use (80% of the total), which is largely allocated in the cultivation of alfalfa for farm animals. “Obviously, when you have a golf course in the desert, where evapotranspiration is going to require you to use more water than in other parts of the state, then you have to pay attention. But when compared to agriculture, domestic consumption is insignificant,” he explains.

While a lightly tapped golf ball rolls along the mowed green toward the hole, 40 miles from Palm Desert the Salton Sea’s water continues to accumulate salt and pollutants. For Mr. Ángel, one of the lake’s biggest threats is that its emissions might drift into the city through the air. Nevertheless, it doesn’t seem to be as frightening as what may be happening to the Salton Sea, given that the many promises for solving the problem have come to naught. The real nightmare is in every house and that is having nothing happen when you turn on a faucet.

We continue to go upriver along the Colorado River, now through the deserts of Nevada. The next stop is Las Vegas, the city of roulettes and unruliness, where we will go to church. We need a miracle.