Photography by Daniele Volpe, text by Lorena Arroyo

“We carry this hood not because we have fears, not because we want you to be afraid of us, because we are compatriots and comrades and, therefore, before you, we take off the hood to show that we are students. You will never be alone.”.

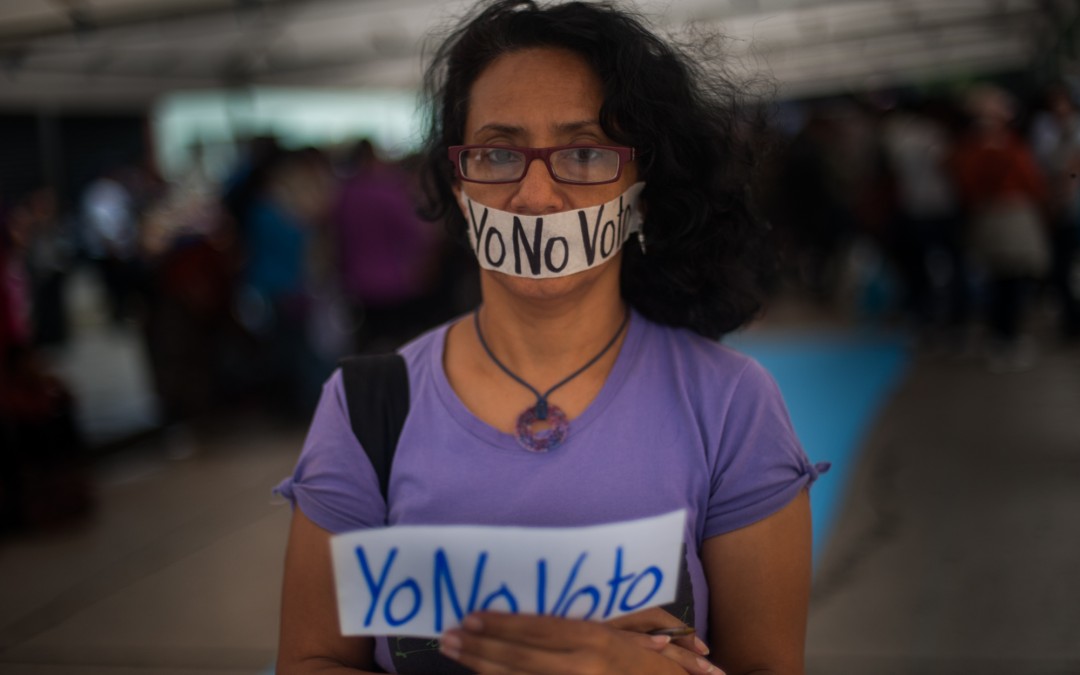

With these words, Tommy Morales, one of the university leaders who went ahead of spontaneous demonstrations against corruption that emerged in Guatemala in April, removed the cap covering his face and his reddish beard before hundreds of demonstrators. He does so as a symbol of the transparency he preaches. “Let’s keep fighting. Do not vote for the same ones. We are in a blank page where we decide what to write. We want you to be aware of your vote and we don’t want to vote for the same people who have trampled us,” says the 26-year old University of San Carlos of Guatemala (USAC) student while being cheered on by other protesters.

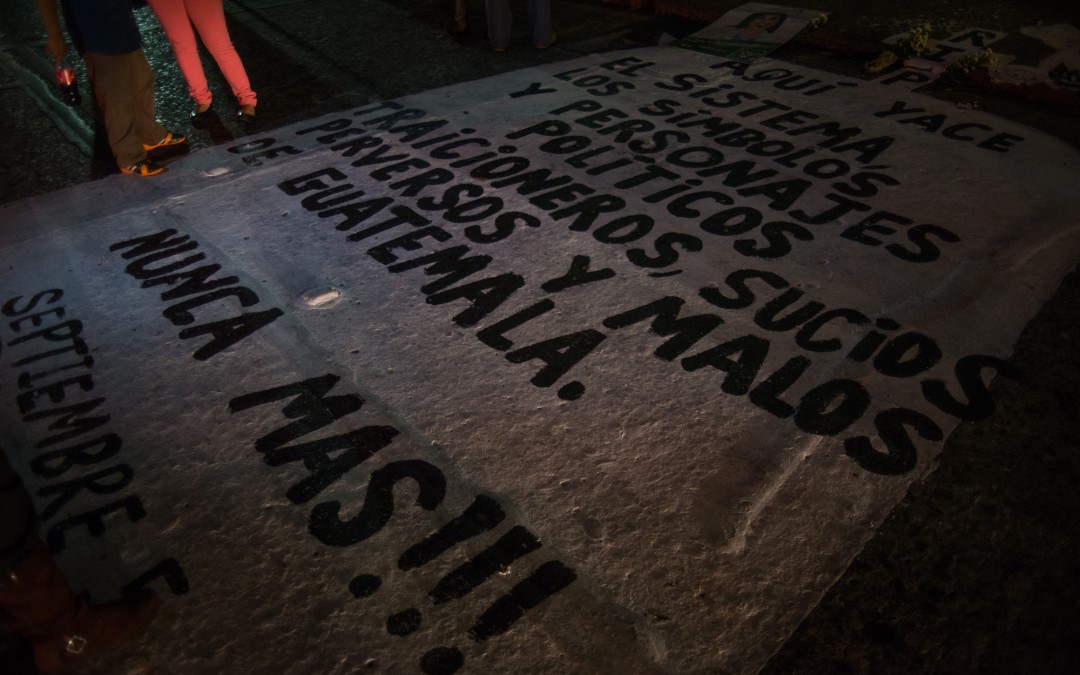

The scene took place in early September, before the first round of elections marked by the fall and imprisonment of the president Otto Perez Molina, accused of corruption a few days before. His resignation was the high point of the investigation of a network of customs fraud called “La Línea” that was embedded in the state and also caused the fall of former Vice President Roxana Baldetti and dozens of other officials. While the former president defended himself in court and citizens celebrated what they saw as a victory for democracy, many Latin Americans looked with some envy that what happened in Guatemala was not being replicated in their countries.

“We are the students standing up for those who cannot … We have the opportunity to be a worthy people, we cannot give the vote to another military”. -Victor Cuellar “el chafa”, 20 years old, a student of architecture.

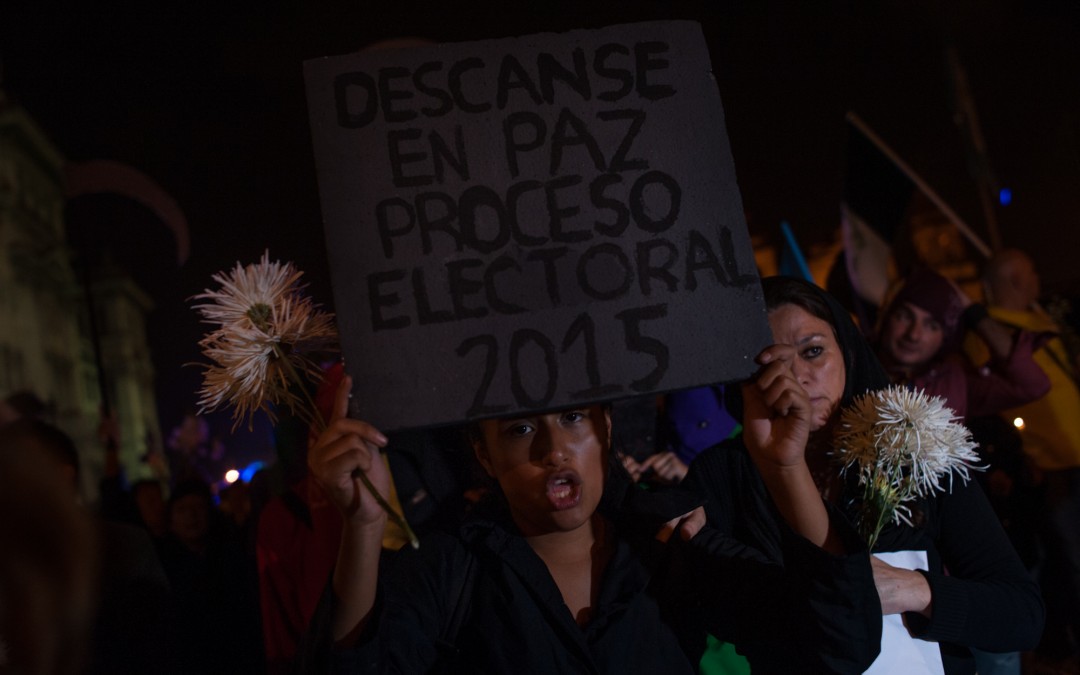

This Sunday, October 25, the country comes to the polls with the hangover of that movement that promised to bury the old state. But the choices of government in the second round go through two candidates with clear links to the past: Jimmy Morales and Sandra Torres . Comedian Jimmy Morales and conservative businessman promises to fight corruption, but has been questioned for former military hardliners supporting his campaign. Despite arriving at the polls without previous political experience, Morales is representative of the Frente Convergencia Nacional (FCN), a nationalist party founded by retired military officers who participated in the Guatemalan conflict (1960-1996), although the candidate ensures that these people no longer are part of his party.

On the other hand, the former first lady Sandra Torres has as the flag of her program to combat poverty and to recover social programs prompted by the government of her ex husband, former President Alvaro Colom. The candidate of the Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (National Unity of Hope) (UNE) divorced Colom in 2011 to run for president, in a move that was questioned as a strategy to guarantee the permanence of the duo in power.

“Many times democracy is unfair. We still have the same people although there is the opportunity to choose,” Tommy Morales, the university leader, laments.

The protests in which Morales took part had a primarily urban base: students, professionals and housewives who came spontaneously to the streets mobilized in part by social media to demand an end to corruption, the collapse of the presidential couple and a reformed electoral system. Some indigenous and community groups, more used to the social struggle, also joined.

“Clearly people are not happy. There is a process of discontent and there are many problems that could not solve the resignation of two people,” the student leader said.

The first round of voting and the wave of popular discontent also resulted in the collapse of one of the candidates who departed as favorites: the right-wing businessman Manuel Baldizón that failed to get sufficient support and denounced irregular acts and evidence of corruption. With his defeat a historical trend in Guatemala was broken: the one dictating that the loser of an election always would be proclaimed winner in the following one. Baldizón had lost in the previous elections against Perez Molina—who now spends his days in the Preventive Detention Center of Matamoros, just outside Guatemala City, accused of participating in “La Linea,” a fraudulent scheme in which customs officials received kickbacks that were distributed inside the government.

The former president was sent to prison just days after hundreds of thousands of citizens demanded his resignation in the largest peaceful demonstration in Guatemala: August 27 hours after the Parliament removed his immunity. By then, there were many signs that pointed to the president and were compiled by the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), a body formed jointly by the UN and the prosecution.

The investigation team led by Colombian Iván Velásquez and a series of press reports that exposed cases of corruption as widespread and showed customs as a fraudulent system controlled by the army since the 1970s lit the wick of popular indignation. ““The presidential band wanted us to silence with the full weight of power, but unexpectedly fell first,”, wrote José Rubén Zamora, the director of El Periódico, in an editorial after Perez Molina lost his immunity.

The political crisis didn’t arrive alone in Guatemala. It was accompanied by a fiscal crisis. . According to an analysis of the National Problems Institute of the University of San Carlos (Ipnusac), the instability that the country experienced impacted on imports, which fell by more than 4% and on the growth of the fiscal deficit. “These are indicators that private investment and consumption are freezing, while the capacity of tax collection continues to deteriorate,” the report said.

Municipal dump in Zone 3, Guatemala City.

The next president will have to deal with that as well as with one of the major ills of Guatemala: the great inequality, which not only shows in the differences between rural and urban areas, but also in the cities themselves, where modern shopping centers and wealthy housing developments live together with slums in the mountains. According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), in Guatemala the poorest 40% had a 12.8% share of the total gross domestic product in 2006, compared with the richest 10% who participated with 39.8%.

What seems clear is that whoever gets the Presidency of Guatemala will face a greater control on the part of the population. “If whoever is elected does not work well, I hope we do not have to wait three years. What we will do from this point is to be actors of complaint. We will not neglect the power of social audit,” the student leader Tommy Morales added.