Photography by Daniele Volpe and text by Lorena Arroyo

With a historical debt—a 36 year-old armed conflict and some 200,000 dead and disappeared—the Guatemalan countryside faces presidential elections on Sunday October 25 with hard to heal wounds.

The most cruel and bloody episodes of the Cold War in Central America, and the only genocide, happened there. The Guatemalan Army fought the Communist guerrillas with full force. The guerrillas emerged in the 1960s in the Eastern Sierras and multiplied throughout the country. Between 1960 and 1996, 626 massacres were recorded.

Most victims (83%, according to the Commission for Historical Clarification) were indigenous Mayans. Many of the executioners were also Mayans. The State (responsible for most of the atrocities—93%, according to the Commission) was devoted to recruiting local youths to form their squads.

The peace accords of December 1996 ended the long conflict and laid the foundations of the new country to be built. First it was necessary to overcome what the Guatemalan writer Rodrigo Rey Rosa called the fear of touching “the tail of the dragon”. That is the expression that an Ixil indigenous he interviewed used to refer to the time in which a sort of pact of silence dominated and there was no talk of the cruelty of genocide. Once the speechlessness was overtaken, came the opening of graves and the taking evidence.

Clyde Snow, one of the forensic anthropologists who participated in exhumations, said he saw more atrocities in Guatemala than in Bosnia or Iraq.

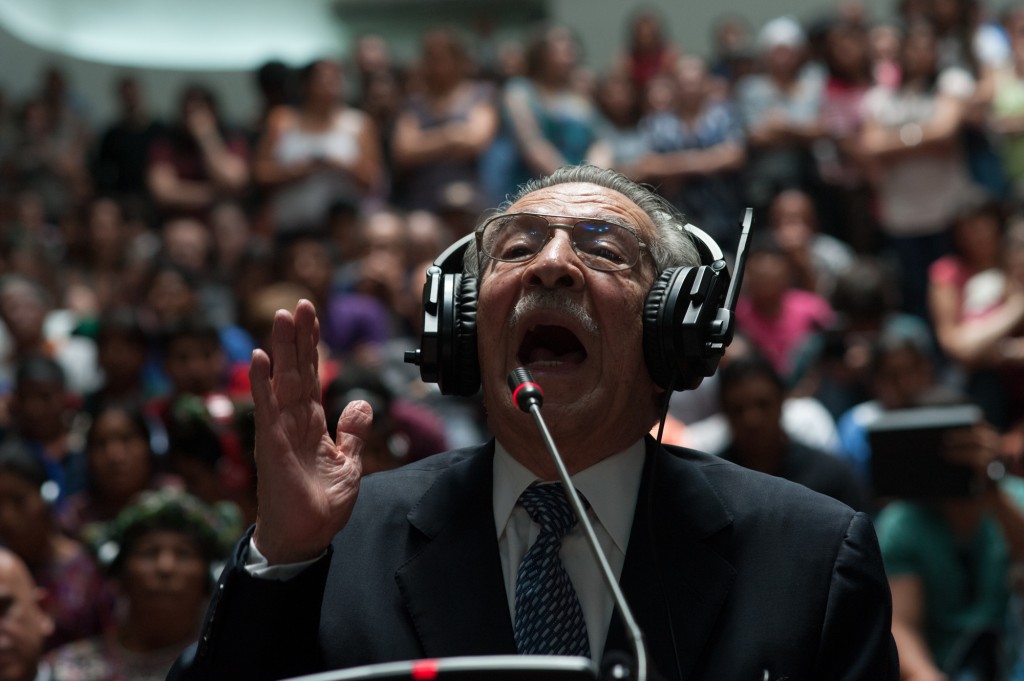

The first outcomes of this work came in 2009 when the Guatemalan courts began to try perpetrators of war crimes. Four years later, in May 2013, the country attended a symbolic sentence. At 86 years old, with hair and mustache gray, Efrain Rios Montt became the first former president to be convicted of genocide by a court in his country.

Before hearing the sentence, the former general heard testimonies like the one from Julio Velasco, an Ixil Indian who recounted his memories by videoconference. When he was only eight years old he saw a group of officers playing football with the head of an elderly woman whom they had beheaded. He also saw others cutting the tongue of those who did not speak Spanish. Rios Montt heard many of those testimonies reported in Ixil language with headphones for simultaneous translation.

Jose Efrain Rios Montt declares during the genocide trail

The man who ruled Guatemala with an iron fist, between 1982 and 1983—the time when there were the worst massacres of the war—was then sentenced to 80 years in prison for the murder of more than 1,700 indigenous people by the army in that period. It was an unprecedented ruling that divided Guatemalans between those who believed that it was genocide and those who didn’t. The Guatemala Constitutional Court overruled it a week later due to “procedural errors”.

Rios Montt was still expecting another trial, but he was declared incapacitated. Unlike the former president, who according to the reports of the experts suffers dementia, farmers do not want to forget.

The wounds of the Guatemalan countryside are not only the ones left by this bloody chapter in its modern history. Rural areas—where most of the 15.5 million Guatemala inhabitants live—also suffer other chronic ills such as poverty and social inequality. And in nearly half of those areas, 75% of the population is poor, according to the latest Map of Rural Poverty.

According to the United Nations Development Program, over 62% of the population lives under the median poverty line across the country. Another 30% survive in extreme poverty. In addition, almost half of the children under the age of five suffer from chronic malnutrition.

Inequality, poverty and violence have made millions of Guatemalans—mainly in the mountains of the municipalities in the west of the country—fleeing in search of better opportunities. Migration to the United States is seen by many as the best solution to face the endemic problems of the country, even if it means falling into debt and risking their lives trying to reach “El Norte” crossing Mexico by land.

It is estimated that about 2 million Guatemalans live in the United States. 60% are undocumented. Paradoxically, immigration to the United States ended up with an unexpected echo in the anti-corruption policy in Guatemala—specifically, the increase in the arrival of unaccompanied minors in the US, 68.000 in 2014, mainly from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. The number of children and adolescents trying to illegally cross the southern US border was unprecedented and sparked a humanitarian crisis for the government of President Barack Obama.

“According to sources close to the US Embassy and the Guatemalan Foreign Ministry, after the massive presence of children on American soil the humanitarian crisis becomes a national security crisis for the US,” a press report from Plaza Pública indicates.

Then, according to the text of Álvaro Velásquez and María Paiz, Washington proposed “to increase social investment in the territories which are the basis of poverty and unemployment” in the Guatemalan highlands. But Americans found that something kept increasing revenues: corruption. “For the US, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) was the perfect tool against government impunity,” they said.

In fact, last January when former President Otto Perez Molina terminated the work of the independent body created by the UN and whose mandate expired on September 15, the US did not hesitate to vigorously defend its permanence. US Vice President Joe Biden led that crusade, for which he traveled to Guatemala and explicitly defended the mandate of CICIG to be extended. While recognizing that that was a sovereign decision of the Guatemalan government, Biden did not hesitate to link the delivery of “billions of dollars” for development—under the US Congress initiative of the Alliance for Prosperity—to the continuity of the Commission.

Last April, a week after the head of CICIG, Iván Velásquez, denounced the dismantling of the network of customs corruption known as “La Línea,” Perez Molina announced the extension of the mandate of the commission until 2017. That investigation led to his resignation and imprisonment due to his alleged involvement in the case, in an unprecedented situation to which massive citizen protests also contributed.

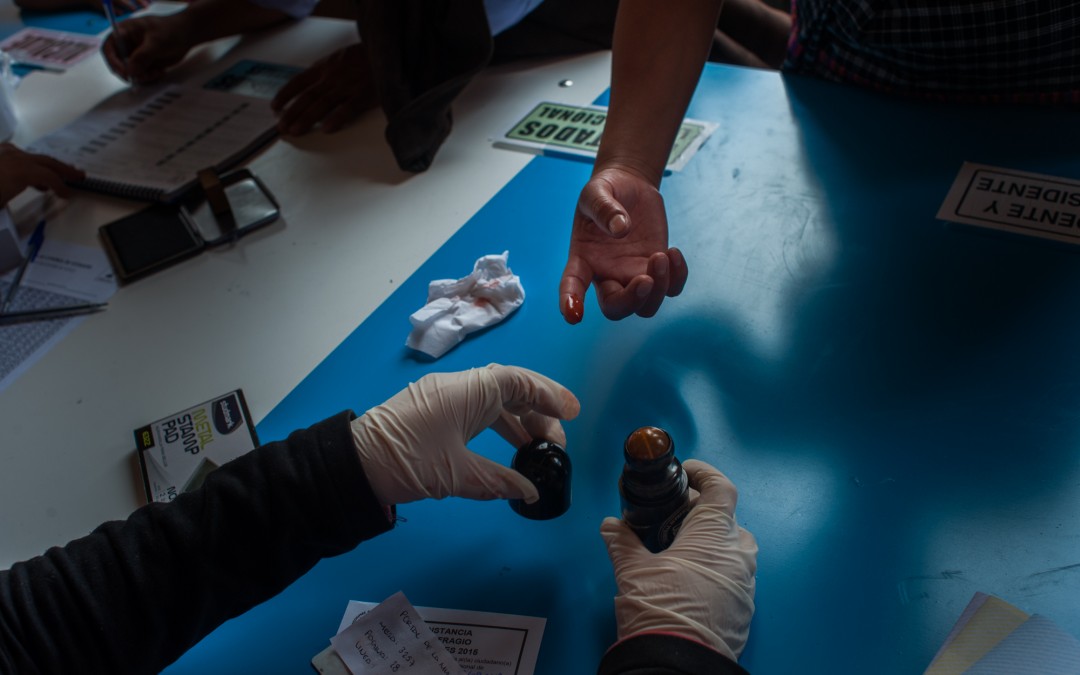

Among the demands of protesters—mainly from urban and student sectors but also with echo in the countryside—was the reform of the electoral law before holding elections. Some demonstrators demanded that people do not vote, but in the first round more than 70% of the 7.5 million Guatemalans registered went to the polls. Indeed, in rural areas it is one of the major developments regarding voter turnout of the last decade.

As Andrés Asier—a journalist at the magazine Contrapoder, —observes in an article, “the voting Guatemala is looking more and more like the real Guatemala” considering that since the peace accords were signed in 1996, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal was at pains to census those who had remained outside the electoral system.

Thus, the department in which the number of voters has grown exponentially is also the poorest one in the country: Alta Verapaz, a vast jungle region with high percentages of indigenous population and where much of the people live very far from the county seat.

But the countryside is still scenario of some of the major electoral challenges, including allegations of “acarreo”—illegal transfer of citizens to the polls— and vote-buying arising election after election.

In San Juan Sacatepequez many voters arrived in buses provided by the parties.

“The truth is that people here come on their own, but some others get transport, they give them lunch at their headquarters and take them to buy their vote. All receive transportation but they take advantage over people in need” said Melvin García, a 58-year resident of the town of San Juan Sacatepequez.

García argues that there are many more polling stations now in the communities, but there are still many places that are not served.

Getting to the polls can be expensive for neighbors.

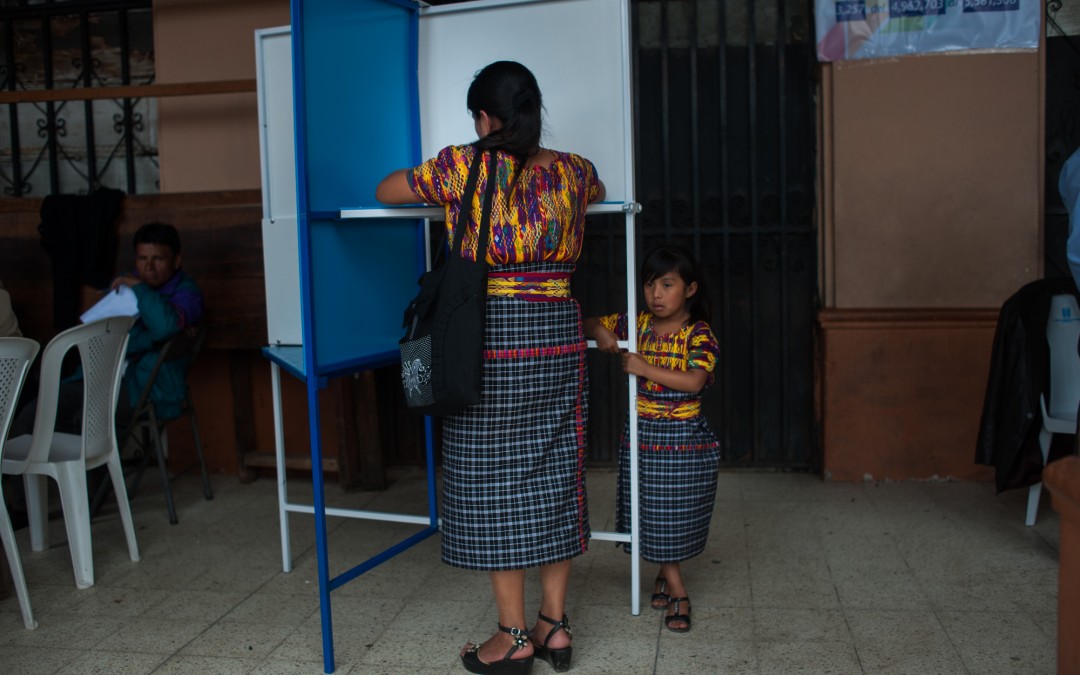

For María Patzán, an indigenous woman from the village of Pachalí with 4 children and pregnant with her fifth child, paying 4 quezales ($ 0.5 US dollars) to reach the nearest polling is too expensive.

In her village she cannot vote, but some campaign teams arrived there.

“Everybody says the same and eventually they don’t deliver on their promises. Sometimes one does not know what to do, whom to vote for if they are all the same,” says Patzán.

“A few political parties came here to promise us things we do not know whether or not they will comply. Nobody knows. God knows who He is going to put to fill the position.”