By Mirna S. Couto

“I have to start over again. I have to adapt my day to doing something related to what I like, to what I know how to do, and to what I do best. Starting over again becomes a personal need.” That’s how Mario Kreutzberger sums up the challenge he imposed on himself following the termination of “Sábado Gigante,” the show which earned him—something he will certainly keep for a long time—the Guinness Record for the world’s longest running variety show during 53 years.

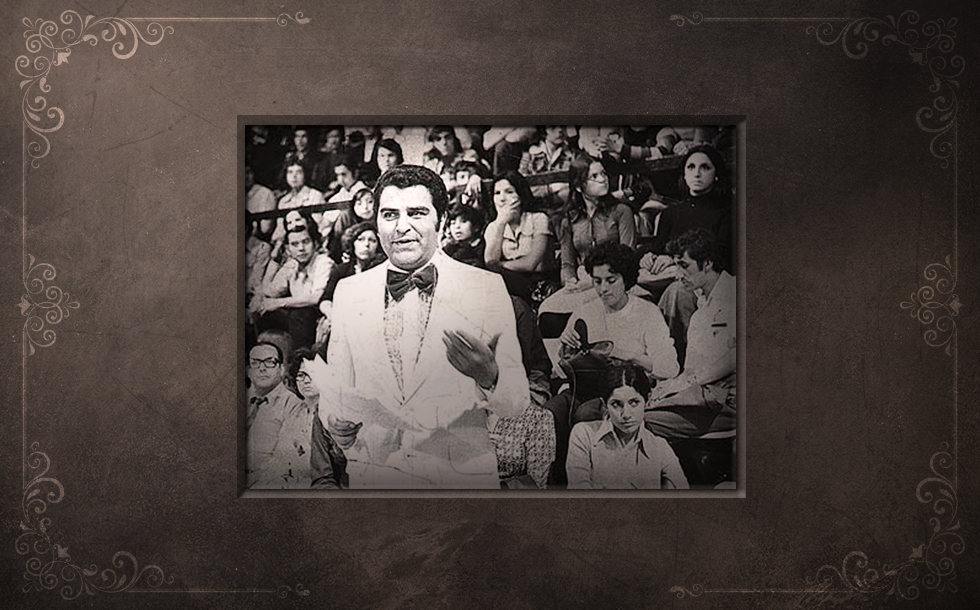

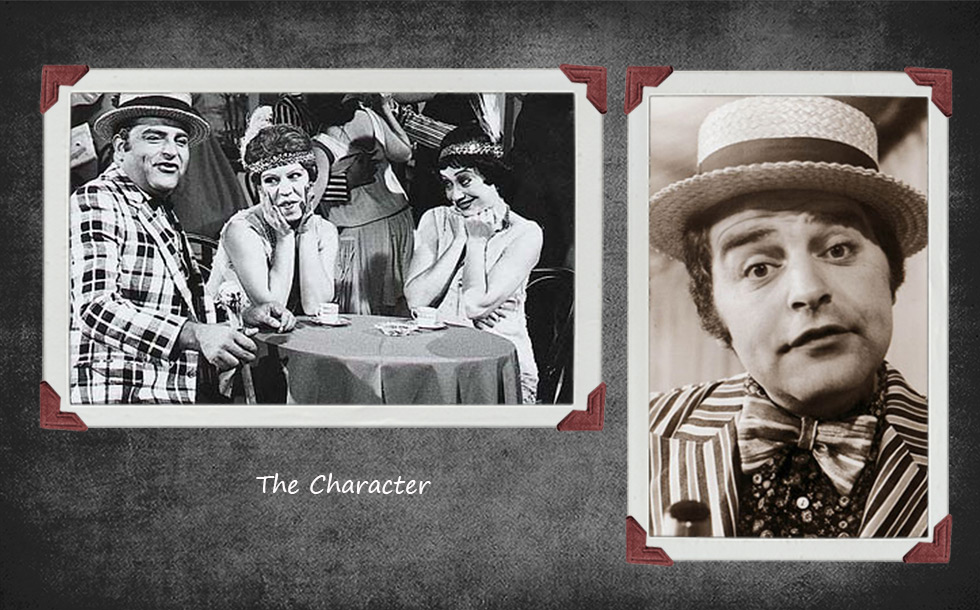

Through Sábado Gigante, Kreutzberger made a legend out of Don Francisco, a beloved TV host admired by millions of followers, also one of the most popular characters on television in Latin America and the United States. But Kreutzberger is much more than the entertainer he played, and his deeds go beyond the small TV-screen, as is demonstrated by Univision News’ documentary El Último Gigante [The Last Giant].

With Sábado Gigante Kreutzberger made Don Francisco a legend, one of the most popular TV characters in Latin America and the United States over the past half century.

In order to accomplish this, the network allocated a TV crew led by Daniel Coronell, Executive Vice President and Executive Director of Univision News. On several occasions we spent some time with Kreutzberger in Chile, his native country, and accompanied him on visits to the places that defined his life, the endeavors that flourished, thanks to his generosity, and the people who had been touched by the magic of his hand and whose lives were forever changed thanks to their having met the popular entertainer.

One of the places we toured was his vineyard, something that would be a dream home for thousands of people. For him, it is just one more obstacle he overcame. When he purchased the plot of land it was in a state of abandonment, riddled with insects, not fit for farming. Ten years of arduous work, together with a team of technicians, with whom he frequently discussed, have accomplished practically a miracle.

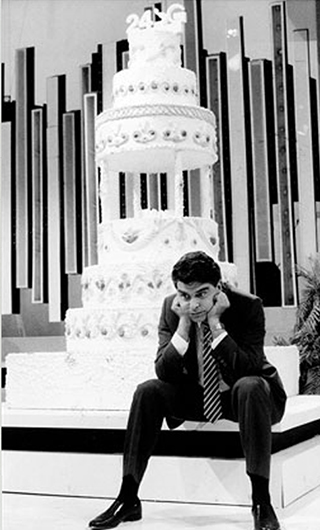

Sábado Gigante entered the Guinness records for being 53 years on the air.

“This year these fields yielded some 200,000 crates of grapes. They were all exportable and they all went to the United States. People must be eating these grapes over there,” he said to us proudly. In a symbolic way, those grapes might represent the fruits of his extraordinary career. Every goal accomplished has had a direct impact, first on his native Chile, then on the United States and later elsewhere in the world. It is impossible to calculate how many people have benefitted from the projects developed by this communications giant. Starting with his most beloved endeavor: la Teletón (the Telethon).

On December 8, 1978 Mario Kreutzberger planted the seed that sprouted in 16 nations of the American continent, giving origin to ORITEL—International Organization of Telethons, in its Spanish acronym—over which he has presided since its founding in 1998, and which serves thousands of children and youth with physical disabilities.

We went with him to the Instituto Teletón in Santiago, where his attention jumped from one topic to the next. He was concerned about how the computers were working, about the youngsters he knew, and about the increase in cases of young victims of gunfire, accidents and other non-congenital causes that require special rehabilitation.

He emphasized the self-sacrifice shown by the doctors, specialists and all the personnel in charge of the facility. He mentioned the criticism faced by the Teletón concept in various countries, and how the 14 institutes in Chile have been growing. Curiously, at no time did he talk about his own contribution to the success of this initiative. He humbly accepted statements of gratitude from patients, relatives and employees, thus minimizing the importance of his own role. Nevertheless, the gleam in his eyes betrayed the fact that those are the best recognitions he can get.

On previous occasions we saw him accepting the Hollywood Walk of Fame Star, being inducted into the Hall of Fame and in dozens of more instances of him receiving international homage, all of which undoubtedly has made him proud. But none sweetened his smile as did these simple displays of affection. This is what motivates him to continue being the “Don Francisco” character, which enables him to raise the funds needed by the cause, and which have made a difference in the lives of many people.

One of them is José Emilio Muñoz, a 44-year-old man whom Mario has known since he first came to the Teletón at the age of 10. José Emilio was born with spastic cerebral palsy and the physicians’ told his parents that he wouldn’t make it through. But they decided to fight for their baby and, to the child’s good fortune, their decision coincided with the birth of Teletón.

Today José Emilio is a Civil Engineer in Informatics, works for the Lottery of Concepción and is an expert in detecting cybercrimes. Even though he continues to receive therapy he is a man that leads a normal life. He speaks in a fluent, friendly and knowledgeable way and one notices the respect he has for “Don Mario.” We observed them speaking, and none of the topics were considered taboo. The subjects ranged from the rigors endured during his rehabilitation to the details of his love life and his desire to have children.

We were moved by such intimate and public interaction taking place before our cameras. José Emilio is also a poet and a writer, a facet he frequently utilizes in order to defend the Teletón organization, which has had its strong ups and downs in recent years. On one of his blogs he indignantly responded to a UN report saying the organization victimized their members while making propaganda for itself—thus causing a great commotion.

Today José Emilio Muñoz is a Civil Engineer in Informatics, works at the lottery of Concepción and is an expert in cybercrime. He continues to receive therapy but leads a normal life.

“The UN has never visited a Teletón center and as far as I know has never solved any problems. Haiti continues to be a failed state, there is still hunger in Africa, human rights are still being violated in many countries throughout the world and the wars are not being stopped. Teletón has done 3 journalistic reports on me. I never felt victimized, nor as if I were being used, nor was I the subject of pity. Thanks to them my inclusion has been total. Everyone who knows me personally is witness to that.

“After watching the broadcast of my reports they have expressed their gratitude to me for sharing my testimony, the manner in which my words motivated them to continue fighting in order to fulfill their goals and that nothing is impossible in life as long as they have the will to live. Is that prompting pity, a diminishment of me as a person, or an infringement against my dignity? Certainly, not,” he wrote in his blog.

Clearly, José Emilio is an example of someone overcoming a hurdle and he assures us over and over again that he was able to develop his potential thanks to an idea from Mario Kreutzberger.

The conversation ended with that reiteration and Kreutzberger began to get ready for continuing his busy schedule, one where working meetings take up practically every minute. “Let’s meet tomorrow at Doña Tina’s restaurant,” he said to us as we said good-bye. At that moment, it had been five months since we had started to video-record the documentary about his life and we had practically become his shadow.

The next day we went to visit a petite woman who lacked schooling but was a millionaire: Agustina Gómez, the owner of the well-known restaurants that bear her name. She received us in a gracious manner, without failing to go into detail about what had been going on around her. We could tell she was anxious to see Mario arrive. She called him her angel, her patron, the man who had helped her to come out ahead, fate would have it, when she found herself having to sell bread, more than 30 years ago.

“He was passing through Arrayán, with his wife and Mandolino. He wanted all the bread loaves I had and told me to bake more, but I didn’t have the money to buy more flour.” Kreutzberger gave her the money and promised to return in a couple of days along with his TV crew so as to include her in his show.

A few minutes later Kreutzberger arrived. Amidst the greetings and embraces they talked about what had been happening since they had last met. The entertainer asked about Martín, the Haitian boy Doña Tina adopted when his mother gave him to her three days after he was born. Despite having had nine children she now says that just now she knows the joy of being a mother. They sat down to talk and the famous bread loaves were brought to their table. A true delight created by this self-taught chef who has already become an authority on Chilean criollo-style cuisine.

It was easy to get lost in the labyrinth of the lively stories being shared. This is our account: She got married and, together with her husband, bought the lot where they set up the restaurant. She had her first child at age 18. She began to sell bread because she had no way to feed the seven children that had already been born at the time she met Kreutzberger. The report presented on Sábado Gigante resulted in the arrival of hundreds of customers and the business began to grow. Just as everything was improving she fell victim to a fraudulent scheme and she ended up in jail. She got out a year later, penniless but the owner of a lot that had been rezoned as an upscale area, at the entrance to an elegant development where Kreutzberger now resides. He invited her to be on the show again and she got back on her own two feet, stronger than before and evermore grateful.

Years later she and her husband began to have their differences and she moved to Miami, working as a cook for a wealthy family. One evening they asked her to come into the dining room to greet a special guest and she found herself face-to-face with Kreutzberger. With his help, and following his advice, she returned to Chile, took in her wayward husband and, after his death, she dedicated herself, body and soul, to her work.

Here comes the moral to the story: She could have sold that lot at any one of those moments of adversity and suddenly become rich, but she chose to fight for her dream. She sacrificed basic comforts. The sheets for her bed consisted of sacks from the flourmill, as she was being as thrifty as she could in order to buy the brocade—a very fancy fiber—for the restaurant’s tablecloths. Doing a good job taking care of her customers, and staying at the place she built with her family is what makes her happy. It’s that simple.

Being a good listener and keeping alive the sense of wonder after some 150,000 interviews seems impossible, but Mario Kreutzberger manages to succeed (or easily entangles us in that illusion).

As she finished telling her story, Kreutzberger looked at her admiringly. He already knew her story, but enjoyed seeing it shared with us, doing what he likes best: changing the ordinary into the extraordinary. Being a good listener and keeping alive the sense of wonder after some 150,000 interviews seems impossible, but he manages to succeed (or entangles us in that illusion).

Again he said good-bye without much ceremony and mentioned several matters that were pending. Once more his mental agility outdid his body, which is about to turn 75. He got up, ready to continue with his menu of appointments.

Another one of the meetings to which we accompanied him was to the home of a journalist who was tortured during the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship. Just like the previous persons, Alberto “El Gato” Gamboa is a character out of a novel. At age 93, he still distinguishes himself by his attractive and penetrating look that earned him the seductive nickname.

We went to visit him, as you can already imagine, because this man had also been touched by the magic of Kreutzberger’s hand. He was director of the daily newspaper “Clarín,” and he had been arrested by the regime and his captors were taking him to Chacabuco, an abandoned saltpeter mine that had been converted into a camp for the detention and execution of prisoners from 1973 to 1975.

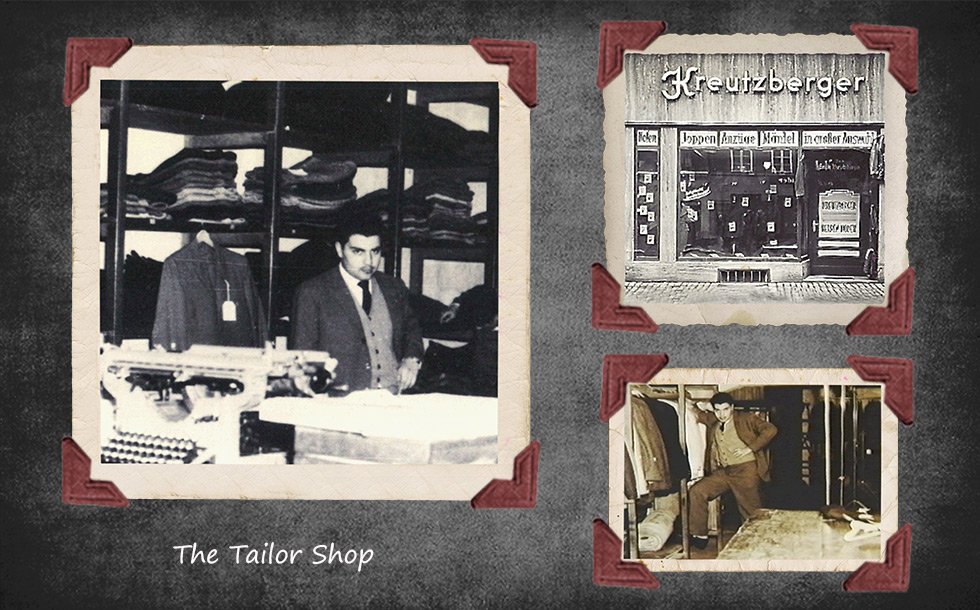

“El Gato” had been tied up in the rear of a pickup truck when Mario—who was going around selling clothes from his father’s garment factory—saw him and asked the military men why they were holding him under those conditions.

This is how “El Gato” recounted it in his memoirs:

“I still cannot understand how Don Francisco managed to be so convincing, such that one of them undid my bindings. He offered me a sandwich, but I did not accept.

During those short moments I again reverted to being a normal man, standing alongside another man who was exceptional, one who lavished me with affection and tenderness.”

Affection and tender mercy are not the first words that come to mind when one sees Kreutzberger. He is a husky and serious man, with a wry sense of humor, one who at the beginning was criticized for offering “circus amusements.” He has clearly overcome obstacles, as have these persons upon whom he has left an indelible mark, and he has not allowed adversities to overwhelm him. He has turned his weaknesses into strengths, to such an extent that many think he could even aspire to be president of his country.

Always dodging praises, he says that popularity must not be confused with preparation. He prefers to use his influence to support social endeavors and to enjoy what he calls those “small spaces” where he can be free from the pressure imposed upon him by “Don Francisco.”

In his search for those spaces, he ventured to embark upon a new project with his eldest grandson, the cinematographer Ilan Numhauser. Together they travel to towns the TV host had visited more than 30 years ago. With an iPad in hand—so as a display for the old images—they go around asking for persons and places he had known way back then. When they find something interesting they stop and video-record it. The result is a program with that breath fresh air that comes from this generation of digital natives, as well as from the wisdom of one who has lived long enough to give complete meaning to the phrase “I have to start over again.”

Four stories drawn from the

Four stories drawn from the