Cruise ship employees work over 70 hours a week, with no rest days or paid vacations. If they suffer any mishaps, they are not protected under the United States justice system.

Matt and Susan Davis were on their way to dinner during their last night aboard the Carnival Ecstasy when they stumbled upon a shocking scene. Blood was dripping down the door of the cruise ship’s tenth-floor elevator. They took out their cell phones and recorded it.

In the video, dated Dec 27, 2015, a female employee can be heard asking guests to leave the area. Forty-five minutes later, the elevator was fenced off behind a floor sign that read: “Sorry, but I’m not working at the moment”.

José Sandoval Opazo, the Chilean-Italian head of maintenance, had been repairing the elevator when it was suddenly activated. The 66-year-old man, who had worked for Carnival for 17 years and was only two months away from retirement, died of brain and skull trauma, according to the family’s lawyer, Julio Ayala.

Because the Carnival Ecstasy vessel is registered in Panama and operates under the Panamanian flag, Sandoval Opazo was subject to that country’s labor laws, which afforded him fewer protections than U.S. laws would.

After his death, his family ended up agreeing to an out-of-court settlement with the cruise line.

“This case demonstrates something which is sadly common, because it happens seven days a week aboard ships,” Ayala told Univision. “Cruise lines say that since they have foreign flags, they are not subject to the regulations of the United States.”

U.S. labor laws don’t govern daily life on cruise ships. Instead, workers are subject to the law of the country of the ship’s flag, and their contracts generally dictate that any labor issues won’t be resolved in court, but through an arbitration panel paid for by the cruise line.

This is what it’s like to work on a cruise ship: contracts of up to nine months, usually with 70-hour weeks, no vacation or days off, no family nearby, no going home at night. Employees live where they work, on a huge ship with an American logo, but often under the flag of Panama or the Bahamas.

A Univision team traveled on two cruises and spoke, both onshore and offshore, with 50 workers whose home port is Miami. For fear of losing their jobs, some preferred not to give their last names or even their first names, the ones they always wear on their badge, whether at sea or on land.

There are few Americans among the nearly 190,000 employees of the largest companies in the business. The cruise industry — with Carnival and Royal Caribbean controlling 70 percent of the world’s market — has found the labor it needs mainly in the developing world.

Most come from Southeast Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean and Eastern Europe. But their contracts usually depend on the country where the ship is registered, among which the Bahamas, Malta and Panama are the most common, according to a database of the cruise industry produced by Columbia University and analyzed by Univision.

A maintenance employee and a cook take a break in a restricted-access zone. Cruises bring together all kinds of workers: waiters, cooks, sellers, musicians, photographers, croupiers, medics, firemen and electricians. Almudena Toral/Univision

On paper, cruise ship employees are protected by a U.S. marine law called the Jones Act. But for a decade workers haven’t been able to file any claims in U.S. courts. Instead, the terms of their contracts with major cruise lines dictate that they must resolve their issues through a private arbitrator, one that’s accepted by both parties, paid for by the cruise line, and based outside of the United States.

It’s the result of a 2006 Court of Appeals ruling on a case called Bautista v. Star Cruises, which became a watershed moment when it determined crew contracts to be the equivalent of commercial contracts. This meant that any U.S. judge could dismiss the claims of crew members whose contracts — as is usually the case — require that they resolve incidents through these independent arbitrators, either in the ship’s flag country or in the worker’s country of origin.

The 2006 court decision “created a new extraterritorial legal space in which the traditional rights of sailors were diminished,” says researcher William C. Terry, who has written several papers on the workforce of cruise lines.

Contracts signed far, far away from Miami

When cruise lines look for employees outside of the United States, they don’t do it directly. Instead they use third-party hiring companies.

“Many times we have seen that cruises bait their ads (…) They promise a crew member a certain type of job and after the person goes through the expenses and the travel effort, they put them in another position.”

“In terms of costs, it is much more expensive to hire [people] based in the United States,” says an employee who was in charge of recruitment at Norwegian Cruise Lines and Carnival headquarters. “When they use international ships, they don’t need to follow our laws. They don’t have to worry about overtime, minimum wage, and other things.”

In Latin America, some of these companies target job seekers who want to improve their English-language skills, through digital ads with titles such as Study English and work on cruise ships.

“The work day is around eight to ten hours,” said an operator of CRC Peru, one of the hiring companies, when asked for information on these jobs. “Your contract will last six to eight months and, at the end, they give you a month and a half or two months of vacation… and then you go out to sea again. The minimum you will earn is $1,000 a month.”

The time off between contracts does not count as vacation time, since it’s unpaid. Workers from several countries in Latin America and Asia interviewed by Univision complained about the difference between what they were told and what they ended up doing on the cruise.

“Many times we’ve seen that cruises bait their ads,” said attorney Jason Margulies, with two decades of experience litigating against large companies. “They promise a crew member a certain type of job and, after the person goes through the expenses and the travel effort, they put them in another position.”

Many workers come to Miami to work. Getting off the plane, they feel the humid air on their skin, they see the concrete highways through the window of a van, and they sleep in a hotel with an unknown roommate. Then, for the first time they climb onto that 15-floor-high marine giant, crowded with thousands of passengers.

Few recall receiving any training before embarking, and many remember the chaos of that first day, when they had to start working just three or four hours after getting on board. They remember getting lost in the hallways, not understanding the scale of their new office at sea.

Un empleado de la limpieza prepara a contrarreloj una cama durante un día de desembarco. Almudena Toral/Univision

Each ship is a small city, as they always say on board. There are waiters, cooks, vendors, musicians, photographers, croupiers, but also doctors, firefighters and electricians. For all of them, an unwritten rule is to always smile at the guests. Always.

A single cruise ship carries around 1,000 employees and more than twice as many passengers. Some of the new sea giants, increasingly large, can have up to 2,500 crew members. In total, Carnival employs about 82,200 crew members on their 99 ships, and Royal Caribbean employs 60,000 on 44 vessels, according to their 2015 annual reports.

A ship stratified by countries

The ship’s central staircase is crowded tonight. Tourists who earlier in the afternoon were clad in bikinis or trunks are now decked out in heels or suit and ties, and skin reddened by sunburn. They observe the dozens of workers present, each holding their nation’s flag and wearing his or her most elegant uniform.

Tonight’s event celebrates the 60 nationalities of the crew. The presenter announces each country of origin and how many of its citizens work on board. Some crew members even do a traditional dance, one from Mexico, another from Colombia.

“And now, the nationality with the most crew members on board: the Philippines, with more than 200 workers!” There’s applause and a Filipino dance. According to various estimates, this country contributes the most employees to the cruise industry.

“That’s it for today! Or, are we missing anyone?” Passengers whistle, shout, and make noise. “Ah! And the United States of America with… 20 workers.”

The ship is the Majesty of the Seas. With some 830 employees, it’s the smallest in the fleet of Royal Caribbean, whose headquarters are located at the port of Miami.

The few U.S. citizen workers seen on ships usually hold positions dealing directly with the public, such as entertainers, singers and actors. They’re better paid and have shorter work hours. It’s also the case with British, Irish, South African and Australian employees.

“Our attitude is if we create the right work environment and create the right growth opportunities we will be able to hire the people we need to hire,” said Carnival CEO Arnold W. Donald in a 2015 interview. With 81,200 employees on vessels and 10,100 on land, Carnival is the largest cruise company on the planet.

“When they use international ships, they don’t need to follow our laws. They don’t have to worry about overtime, minimum wage, and other things.”

“Do you find them locally or bring them in from other locations?” asked the journalist from WLRN, a radio station based in Miami.

“We do both. We hire locally obviously. We’ve been able to attract the talent at the entry levels and above that locally and, of course, people all over the country who want to relocate here,” said Donald.

He did not mention Carnival’s enormous international roster, and he did not clarify if he was referring only to the company’s land-based offices. Because on the ships, that’s not how things are perceived.

Several university researchers have written about alleged “stratification” by nationalities on cruise ships, or of a “hierarchy” of ethnic groups. The sociologist Christine Chin, author of the book Mini United Nations: Crew on Cruise Ships, details an organization of labor that goes hand in hand with employee nationality, ethnicity, and gender.

Aboard a Carnival ship, for example, workers themselves admit divisions by origin and ethnic groups. For $40, the company offers passengers a tour through the bowels of the ship without a camera, phone or recorder, and requires them to pass through a metal detector for safety reasons.

On one of these tours, the guide openly refers to this issue: every nationality dominates a section of the ship, whether it’s because of the hiring process, affinities between nationalities, or skills according to country of origin.

That was obvious in the bowels of the Carnival Ecstasy. Indians dominated the kitchen, Indonesians were in the refrigeration and laundry areas, Filipinos in the hotel rooms, Caribbean and Central Americans in maintenance, Italians in the control rooms, and at the casino, Eastern Europeans cut the decks of cards.

Este haitiano lleva 23 años en el mar, 18 de ellos con Carnival. Sigue en el mismo puesto de mantenimiento que su primer día de trabajo y con el sueldo casi idéntico, que no llega a los 1,000 dólares. La mayor parte de su salario lo destina a su esposa y sus cinco hijos para pagar “universidad, agua, comida y medicinas”.

“A worker from the first world, where there are better wages, will not go on a cruise to earn the same or less than on land, with a heavy eight to fourteen hour-a-day work load and no days off,” says Aaron, a Venezuelan who lives in the U.S. and used to work in the excursion department of a large ship.

Carlos Orta, vice president of corporate affairs for Carnival, told Univision News that “people who want to work can apply from anywhere in the world. We are one of the most diverse companies in the world. Everyone is treated equally.”

Asked about the fact that employees are subject to the laws of their country of origin and that of the ship’s flag, Orta replied: “I’m not sure, I don’t know about the contracts.”

A financial life vest

Salary is a taboo subject for many workers. “It’s our secret,” was the casual comment of a few 20-something Indonesians at a Miami coffee shop where they usually go to rest and eat food from home.

A base salary for cruise-ship employees can range from between $1,000 and $1,500 a month, according to several studies, interviews and consultations with industry professionals. For the more invisible jobs, such as in laundry or the warehouse, it can be around $600.

Those who depend on tips have more problems. Wages for them are minimal – about $500 a month, and for some waiters just $50 – because it is expected they’ll make much of their money from tips. Some workers say that years ago they used to make $2,000 and $3,000 a month, but lately, tips have shrunk.

On the one hand, cruise lines include a mandatory gratuity per person per day on the passenger’s bill, which reduces tipping generosity when finishing dinner or drinks. On the other, the globalization of the cruise ship industry has resulted in low-cost tickets, last-minute offers and no cash on passengers while aboard.

Wages on these ships are far below the U.S. average, but they are higher than those in India, Mexico, Colombia and the Philippines.

“We are like little ants, our mission is to save – to save for six months of work to cover the family expenses and the three months of holiday without pay,” says Shahid, a waiter who showers guests in kindness, opening the napkin on their laps and singing Happy birthday to you at the top of his lungs.

For a quarter century, Shahid has been working on the high seas. He says that were it not for the ships, he wouldn’t have been able to afford a decent university for his children, nor a private school for his grandchildren in Pakistan. If he calls home from the ship, he has to pay a small fortune for a three-minute conversation; he prefers to call them from dry land, with a SIM card he bought in Miami.

Shahid confesses he has become inseparable with a Sicilian who serves customers with a wide smile, and then turns around and fights with other employees. Shahid has already internalized the round-the-clock work schedule, the physical toughness of the job, and the pressure caused by passenger satisfaction surveys.

What lies behind the smile

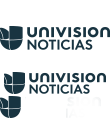

Workers with just a few contracts under their belts don’t deal with life on the high seas so well. The ship, which helps them send money to their families, is also sometimes a pressure cooker of competition, of love triangles, of living with strangers in narrow, windowless cabins and bunk beds for two or three people.

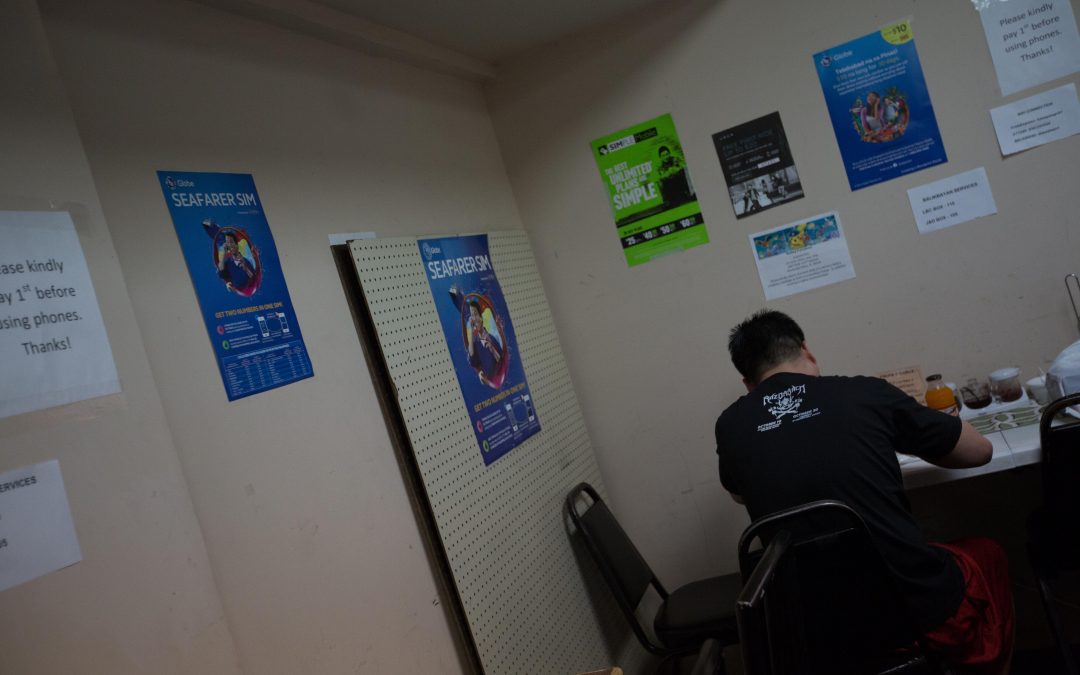

Un trabajador de mantenimiento se prepara para echar el ancla del Majesty of the Seas de Royal Caribbean al llegar a Bahamas. Almudena Toral/Univision

Carolina, a 33-year-old Colombian woman who joined up to meet people, explore the world and practice English, recalls tensions in her cabin and at work: “It’s absurd how they treat you, as if you were some kind of animal. I had to complain about three guys because they were driving me crazy with sexual harassment every single day.”

In 2013, three British researchers published an article entitled Sexual Risk Among Cruise Ship Workers, after interviewing some 200 employees on this issue in Florida. In a markedly masculine environment, 35 percent of the women surveyed were worried about sexual harassment aboard the ship.

The authors noted a risk of harassment by superiors, multiple changes in sexual partners, and even finding a lover for protection against other crew members. Cruise lines prohibit employees having sex with passengers, but not with co-workers.

“It is common to see both guys and girls getting into fist fights over girlfriends, boyfriends, or lovers,” says Carolina. But that wasn’t her main source of trouble during the cruise. It was her own hands.

A hospital at the office

According to Carolina, she went to see the ship’s doctor on several occasions. She showed him her swollen hands and complained that they were numb, that she couldn’t pick up a glass of water without spilling it, and that she had pain all the way up to her shoulder.

She finally was able to get off the ship in Miami, where a doctor hired by the company at Mount Sinai Hospital told her she was suffering from Carpal Tunnel syndrome in both hands and that she needed immediate surgery.

Carpal Tunnel is a common condition among cruise-ship workers. The company covered the medical costs of Carolina’s surgeries and months of rehabilitation. Univision News attempted to discuss this case with the doctor, the hospital and the cruise line, but they all declined to comment on the matter.

Cruise ships typically offer medical consultations at a small clinic below deck, with a specific schedule of visits and medical professionals commonly from outside the United States. On the Carnival Ecstasy ship, for example, the clinic is small and has a waiting room shared by tourists and employees.

There are cases apparently more complicated than Carolina’s. Earlier this year, lawyer Julio Ayala went to court for a female Filipino worker who suffered complications from gallbladder stones, and ended up having eight surgeries.

La mano de Carolina, una trabajadora de crucero que cargaba platos en comedores, meses después de salir del barco con túnel del carpo severo. Almudena Toral/Univision

The defense said that the employee had warned of her problem while in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, but that she did not see a land-based doctor until seven days later in Cozumel, Mexico. “They performed a surgery that nearly killed her,” says Ayala. The complications resulted in five other operations in Mexico and two more in the Philippines.

“In order to avoid the expense, [the cruise lines] prefer to take the risk of sending patients to foreign ports where medical attention costs a fraction,” adds Ayala, who worked as a lawyer for Carnival for two decades.

Weeks after the Univision interview with the lawyer, the woman’s case went to court. With one vote against (and seven in favor of the worker), there was no unanimous resolution. As in the majority of cases, the prosecutors came to an out-of-court settlement with the cruise line. The figure is confidential.

The lawyer mentioned another case: a Filipino woman who noticed something odd on her chest. The attorney and her client claim that she was examined in Mexico, where doctors didn’t detect any tumors. Four months later she was examined again in Miami: she had stage-four cancer and underwent double mastectomy.

“It’s yet another sad case showing how tragedies can happen to crewmembers when [companies] don’t want to spend money on medical attention,” says the lawyer. He affirms that medical training and sanitary processes are of poorer quality when employees receive care abroad.

A viral but confidential death

The bloody video recorded after José Sandoval Opazo’s death aboard the Carnival Ecstasy was viewed hundreds of thousands of times on social networks.

His family in Italy hired Ayala and his Miami-based law firm, one that’s advertised as “crew advocacy.” Ayala places ads in the vans carrying workers around Miami during their time off, distributes pens with the name of his website in the bars where employees go to blow off steam, and has an active Facebook group. The industry has publicly accused these firms of demonizing the cruise-ship business and enriching themselves at their expense.

Miami’s downtown is full of these law firms, dealing with the labor problems of cruise industry workers. The lawyers in these firms are acquainted with the legal teams of cruise lines, and even exchange text messages with them.

Sandoval Opazo had two months left before retirement when he died in the elevator. According to his family’s lawyer, Carnival concluded that the cause was human error by the employee. The family in Italy and the lawyer in Miami finally gave up on the idea of going to trial for lack of other testimonies. Compensation under maritime law is minimal, so they discarded the option of going to court.

The authorities will not investigate his death. The family reached a settlement with Carnival. It’s also confidential.