Ships are cities with no police or 911 emergency hotlines. When a crime occurs, the crew members are the ones who investigate and elaborate the only available statistics.

Alyssa’s woke up little by little. It started with a powerful back pain that rose to her neck and head. “What happened?” she asked herself woozily as she was driven home following a vacation cruise to Mexico.

She lifted up her dress and saw hundreds of bruises on her legs. Two artificial nails were missing from her fingers. But she had no memory of her last night of partying on the high seas. When she looked down, her ankles were swollen. Everything hurt. She remembered nothing.

“I could not believe that’s what my body looked like,” Alyssa said in an interview with Univision.

She had spent four nights and five days on a cruise to Mexico with her teenage daughter, her mother and two girlfriends. Everything was fine until the last night. The others went to sleep, but she stayed a while longer at the casino bar. Two men – one of them white, tall and muscular, the other short and Hispanic – joined her. She drank the last Jack Daniels and coke of the night – which passed through several hands before reaching hers – got up from her chair and tried to leave.

“That’s the last thing she remembered,” said the report filed later by the police in Fort Worth, Texas. It added that she was the victim of a “sexual assault.”

A crime on the high seas is not the same as a crime on land. There’s no 911 to call in case of emergencies, and police cannot rush to the scene. The cruise companies are in charge of security aboard their ships.

There are hundreds of people like Alyssa each year – victims of crimes committed aboard cruise ships that dock in U.S. ports.

None of the three leading cruise companies responded to multiple Univision requests for detailed interviews and comments for this story. Univision was able to talk briefly to two senior executives from Carnival Cruise Line, including CEO Arnold W. Donald, during an event at the Port of Miami in May, but they declined to sit down for longer interviews.

The Cruise Vessel Security and Safety Act (CVSSA), approved by Congress in 2010, requires cruise companies to keep a record of complaints of crimes committed on board as well as making available to the public – and the FBI – the information on nine categories: homicides, suspicious deaths, attacks with serious injuries, kidnappings, fires, damage to the ships, thefts of more than $10,000, disappearances – and sexual assaults, against both adults and children, including cases where victims are drugs.

But the requirement to report the crimes applies only when the victims are U.S. citizens.

When a victim reports an onboard crime, it’s the cruise line’s own security employees and not public officials who carry out the first look into a crime scene and collect evidence. In some cases, they preserve the evidence until the ship docks.

“You can have two to 2-5,000 people on these ships and you really don’t have a police force. You don’t have hospitals. You don’t have public safety fire people. You don’t have that on a cruise ship and yet you have as many people on a ship as you would do living in a city,” said Rep. Doris Matsui, a California Democrat and a sponsor of the CVSSA.

Most victims are not aware that if they are U.S. citizens they can immediately call the FBI, police or the U.S. embassy at the next port of call because the law requires cruise ships to provide direct and free telephone lines for victims.

Those who are not U.S. citizens, however, can only report the crimes to authorities in the country where the cruise ship is registered. There’s no guarantee their complaints will be investigated.

According to CLIA, its associates are required to report all incidents occurring on ships that depart from or arrive in any port in the United States to relevant authorities, regardless of the nationalities of the parties involved.

When victims report a crime aboard a cruise ship, it is the cruise lines’ own security staffers, not government officials, who conduct the initial investigations and collect evidence. In some cases, they hold on to the evidence until the ships dock. Almudena Toral/Univision

A database created by Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in New York and reviewed by Univision Noticias shows that out of 265 cruise ships active around the world, only one is registered in the United States. The majority of the vessels are registered in the Bahamas (33%), Malta (13.9%) and Panama (13.5%). Victims of crimes aboard those ships must rely on law enforcement agencies in those countries.

No one explained to Alyssa what she should do. She did not wake up in her own cabin the morning the ship docked. She doesn’t even remember where she was when she opened her eyes. Her worried family reported her missing to ship officials when they noticed she had not slept in her own bed. A crewman accompanied her to her cabin – still under the effects of some type of drug – and pushed her to pack quickly so the ship would stay on schedule. Relatives recall the crewman telling them, “Get off the ship. Get off the ship. You are already running late.”

Alyssa was not asked about her disappearance, and she did not file a complaint while still on board. The crime scene was not processed and there was no medical exam for evidence of rape. Nothing was done.

Matsui talked about the difficulties that victims of onboard crimes faced before the CVSSA was approved, especially the 2006 rape of another woman, Laurie Dishman.

“She expected to have medical assistance. She expected to be able to report it to the authorities in a timely manner. And none of that really happened at all,” Matsui told Univision. “When she went back (to the United States), they went to the port, reported to the FBI, but nothing really happened.”

“She needed to have their medical records from the ship and nothing was available at all (…) The FBI couldn’t do much without any evidence and so she came to me to tell her story,” she added.

A family looks out to sea aboard a Carnival cruise ship. Almudena Toral/Univision

The preamble to the CVSSA notes that in the five years before the law was approved, the lack of data and the legal vacuum for crimes at sea had made it difficult to apply specific procedures for crimes and left passengers highly vulnerable. At that time, sexual and physical assaults topped the list of crimes investigated by the FBI.

Dark numbers

The number and types of crimes at sea are a tiny fraction of what happens on land, said André Picciuro, a consultant with Cruise Line International Association (CLIA), the leading association of cruise ship companies. Just two of its members, Carnival and Royal Caribbean, control 70 percent of the world market.

CLIA supports its argument that cruises are safe by citing a 2015 study by criminologist James Alan Fox. In 2015, Fox conducted a comparison of crime rates in a city versus a ship, based on FBI crime statistics on land versus reports by four cruise companies, occurring between July 2012 and December 2014.

Fox only compared three types of crimes: murder, rape and assault with serious injury. He concluded that, for example, the rate of violations on board is 8.6 per 100,000 people, compared to 24.7 per 100,000 people across the United States. “It is 65% lower than the total for the country,” he writes.

The study did not include reports of all crimes made by the cruise companies and left out five categories of crimes that should be recorded under US law. On board incident books that the cruise companies delivered to the FBI in 2011, a copy of which was obtained by Univision, show that other offenses occurring on the high seas, mostly of a sexual character, are excluded from voluntary reports published by the companies on their websites .

In 2014, the Office Accountability US Government (GAO) questioned the use only of FBI data to measure the problem.

Because crimes not investigated were never counted, a large number of complaints were omitted from the records, the GAO said. Secondly, the slow pace of the judicial process means that some cases can take months, even years, before they are added to the tally, it added. Furthermore, the comparison used crime rates from larger urban areas, rather than cities of 3,000 people, similar to the population of cruise ships, it said.

A 2013 Congressional report prepared for Democratic Sen. John Rockefeller showed the Coast Guard database reported only 31 crimes aboard cruise ships since 2011. But those were only the cases solved. Cruise lines reported 959 complaints of crimes to the FBI during the same period.

The report also noted that crimes against minors “are unrepresented in publicly available statistics” even though the ships’ records – which were not published – indicated they accounted for “a significant percentage of total alleged sexual assaults.”

Maritime lawyer James Walker said that although crimes can happen at sea or on land, “the cruise lines want to take the position that crime didn’t occur” because “they don’t want to be portrayed as a lawless floating island.”

Analysis of the crimes

Univision analyzed the lists of crimes recorded in the logs of the cruise lines and reported to the FBI in 2011 – the first year after the CVSSA went into effect.

The data included all the crimes reported aboard the ships and not just the number of cases solved.

A crime that takes place on the high seas is not the same as a crime on land. Passengers can’t call 911 in an emergency, and police can’t arrive at the crime scene within minutes when the ship is in the middle of nowhere. The cruise lines are in charge of security. Almudena Toral/Univision

The records showed that in 2011 there were 563 crimes reported. Fights and brawls accounted for about half of the cases (248), and one-third (149) were sexual in nature, the majority of them improper touching followed by rapes and sexual assaults.

Twenty of the sexual crimes involved minors. One of the reports was of a teenage girl who accompanied a young man to his cabin to get a coat so they could watch the stars on the night of March 6 2011. He allegedly raped her, then threatened her. “The subject told her that if she mentions this incident to anyone then he would find her,” the report noted.

One of the best-known cases involved Paul Trotter, a playground supervisor accused of sexually abusing 13 British and two U.S. children between 2007 and 2011 aboard two vessels operated by the Carnival-owned Cunard line – the Queen Mary II and the Queen Elizabeth.

Trotter was accused of 13 sexual assaults as well as taking pornographic images of minors. He pleaded guilty.

The records for 2011 analyzed by Univision showed 18 cases of rape, 14 cases of coerced sex and 15 others without penetration. Complaints of indecent exposure, sexual misconduct and other types of improper contact completed the list of 149 sexual crimes.

Minors make up a “significant percentage” of the victims of sexual assaults aboard cruise ships, according to a congressional report from 2013. Almudena Toral/Univisio

Women made up 87.5 percent of the victims of sexual assaults and abuses. All the aggressors were men. The majority of the assaults took place between 7pm and 6am on ships operated by Carnival and Royal Caribbean, especially the Carnival Liberty and Monarch of the Seas, both large ships with capacity of more than 2,500 passengers.

In Alyssa’s case, she was attacked sometime after 3 am. She believes her assailants were two passengers she met during a stop in Cozumel, Mexico, and then again at the casino bar on the last night of the trip.

The records reviewed by Univision News showed nearly two thirds of the attackers identified were passengers, and the rest were crew members.

The number of crimes recorded by the Coast Guard around the same time is much lower, even though its reporting period is longer, from January 2010 to September 2015.

During that same time the FBI closed only 153 cases of crime aboard cruise ships. Of those, 66% of the cases were sexual assaults, followed by assaults with serious injuries, suspicious deaths, thefts of more than $10,000, the disappearances of two U.S. citizens and one case of damage to the ship.

The majority of the sexual assaults were recorded by Carnival ships, followed by Royal Caribbean vessels – likely due to the fact that the two companies operate the most ships.

Univision interviewed 8 victims of rape. In none of the cases was the attacker arrested. Most were settled with payments by the cruise companies accompanied by confidentiality agreements that forbid victims from revealing the names of the ships, their stories and the amount of money they were paid.

Jason Margulies, a lawyer with a Miami firm that handles many lawsuits against cruise companies, said few charges are ever filed and few attackers are ever arrested. He knows of accused crew members who were fired by one cruise line and then hired by another, or remained working on the same ship while a case was investigated.

Such soft responses, Margulies added, allows attackers to believe the worst that could happen to them is that they would be put ashore at the next port of call, or that if they are employees they would simply be sent home.

U.S. government records accessed by Univision show the FBI opened 18 investigations for crimes aboard cruise ships in 2012, but arrested only four suspects. Another five were charged, and only four were convicted. In 2013, the FBI opened 41 cases, detained four suspects, charged four and won convictions in three cases.

Univision asked several times to interview FBI agents who handle onboard crimes, to learn more about those figures and how the agency investigates crimes at sea. The requests were not granted.

Feeling defenseless before the CVSSA was approved, victims of crimes aboard cruise ships created the International Cruise Victims Association. It started with the cases of four U.S. families, and now has grown to 25 countries.

Kendall Carver was one of the association’s founders, as well as a promoter of the CVSSA. His daughter disappeared from a Royal Caribbean vessel in Alaska in August 2004. He never learned what happened to her, and only three years later did the company admit it had a video of the last time she was seen.

Carver now advises victims, including those who are not U.S. citizens and have to report to law enforcement agencies in other countries. The group also documents cases on its Website, so the public is aware of what can happen on a cruise.

A call to nowhere

In the months after her attack, Alyssa combined her normal life – taking her two sons to school, working, caring for the son of a friend – with a pursuit of her case, including numerous calls to the cruise line.

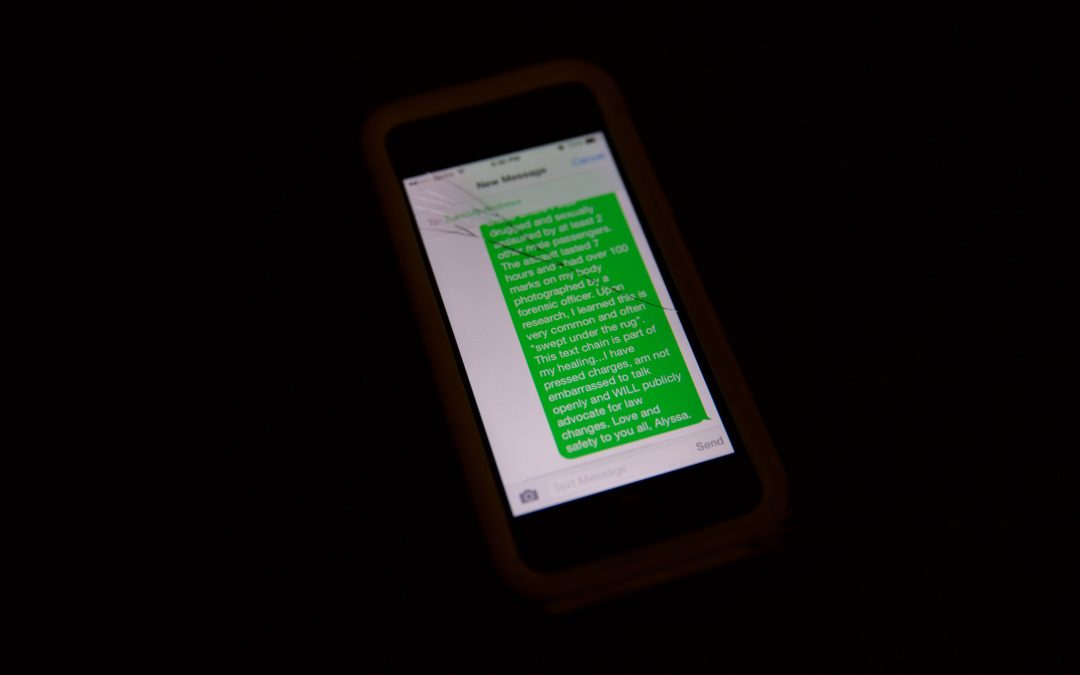

“I am calling just to ask about the status of my sexual assault case that occurred on the ship,” Alyssa told an employee of one of the two leading cruise lines, in a phone call witnessed by Univision.

“ So it looks like it was escalated. And it looks like the authorities will be reaching out to you,” the woman answered.

Alyssa is accustomed to waiting. After that call, she never heard again from the cruise line.

“OK,” Alyssa responded. “What will the company do?” she asked “I have had one call from an FBI agent. But it’s been 47 days since the incident and I haven’t heard from anyone at the cruise line.”

The cruise line employee responded: “We have to escalate it. So it’s out of our hands. There’s nothing else that we could do.”

Alyssa insisted: “OK. And what about, like, as far as the cameras that are on board, because, you know, my body was physically missing for seven to eight hours, and I was brutally beaten and sexually assaulted.”

The woman replied: “Yeah, understood. I mean that’s why it’s been escalated. It’s nothing we’re handling here.”

After Alyssa inquired about the video recordings, the woman said cameras are “not like a policy by the state or anything” adding that “all the security cameras in every area are not really required.” The CVSSA, however, does require all cruise ships to have video monitoring systems that can document crimes and serve as evidence.

The FBI took on her case a few months ago, and it is investigating. She’s expecting a court date around the end of 2016. She hopes to see her two attackers convicted. And then she plans to file a lawsuit against the cruise line.

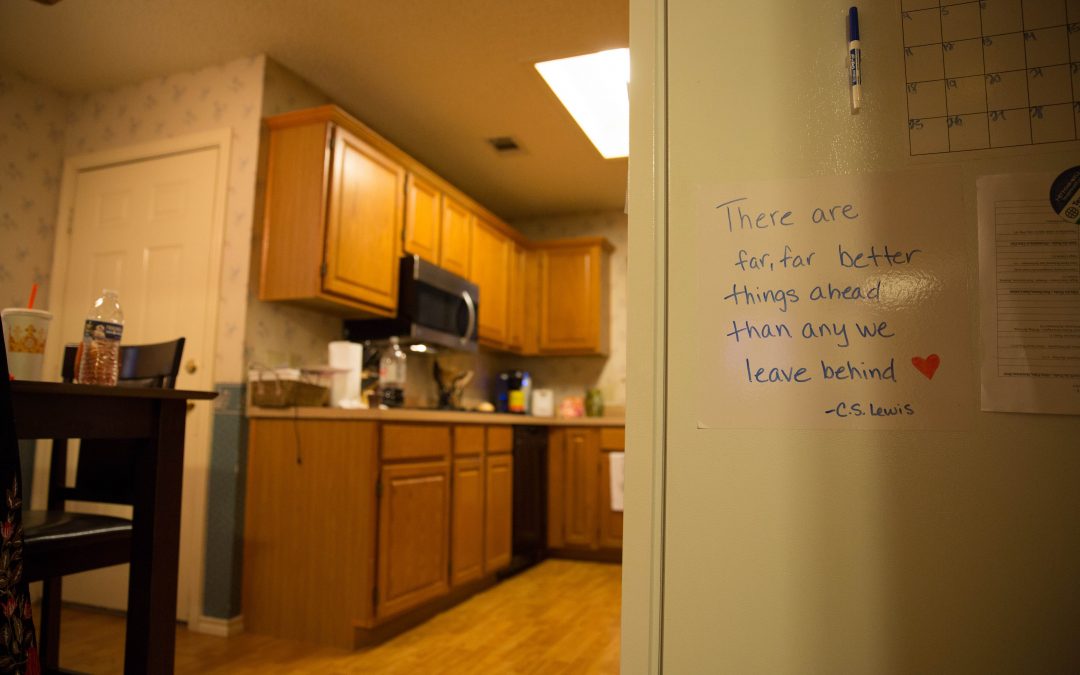

Alyssa now has locks on all the doors of her home, and makes sure they are locked. She’s also taking personal defense classes from a friend who is a policeman and is teaching her to break out of an attacker’s hold. Her sons are also taking the classes because she wants them to know how to defend themselves.

She’s also going to therapy. She wants to forget the bruises she saw when she stood naked before a mirror that morning. She wants to forget the physical sensation that confirmed to her that she had been raped. She wants to stop remembering the faces of the two men every time she looks at her body. She is afraid.

Lawyers and experts consulted by Univision agreed that the high level of alcohol consumption aboard cruise ships is one of the elements that encourages crime.

“There’s a direct correlation between alcohol and bad things happening … There is an unbelievable amount of alcohol around cruise ships,” said Walker. He added that he knows of some victims who were served more than 20 drinks in four to five hours.

Margulies said bartenders are trained to encourage the sale of drinks, not to stop those who have had too many. “They’re trying to get up onboard revenue, get those people to spend as much money as they can onboard,” he said. “And the two places that they do that are in the casino and at the bars.”

The sale of alcoholic drinks and gambling are two of the top revenue streams for cruise lines, according to the annual reports by Carnival, Royal Caribbean and Norwegian.

That’s why cruise ship bars often display signs urging travelers to drink. “Anecdotes are 17% funnier with a drink,” said one of the signs.

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that a study by criminologist James Alan Fox was compiled with FBI data on closed cases on board cruise ships. Fox’s study used data provided by the cruise lines on alleged crimes committed on board.