After moving from California to Oregon, Maynard took life-ending medication prescribed by her doctor and ended her life on November 1st 2014. On her death certificate, it is written that she died of brain cancer. Less than one year later, California legalized aid-in-dying.

By Mara Van Ells, Naomi Nishihara, Nina Yanni Zou and Nadine Sebai*

On Oct. 5, California Governor Jerry Brown signed the End of Life Option Act into law, making California the fifth state in the U.S. to legalize aid-in-dying.

Since Brittany Maynard, a California woman in her late 20s, moved to Oregon in order to die, the concept of aid-in-dying spread across the United States. In Oregon, terminally ill patients with six months or less to live can request life-ending medication from their doctors since 1994.

Maynard was diagnosed with a brain tumor in early 2014, and before moving to Oregon, she endured an unsuccessful surgery. Her widower, Dan Diaz, said they spent months researching clinical trials, trying to find new treatments and a way to stop her tumor’s growth. Ultimately, they found nothing.

Dan Diaz, Brittany Maynard’s widower, holds his wedding photo at his home in Alamo, California.

The couple knew the brain tumor would cause immense suffering, and Diaz said his wife refused to die that way. Her story went viral after she released a video about her choice to move to Oregon to take the medication.

“That decision, that idea that we had to move, that was really what got Brittany to speak up,” Diaz said. “That was the crux of the whole thing for her. We had to load up a U-Haul with all of our belongings, and she would say ‘Why do we have to drive 600 miles north, just so I can die peacefully?’”

Maynard moved to Oregon to establish residency, and was later joined by Diaz and her parents. They spent the remaining months of her life traveling and spending time outdoors with their dogs. “She wouldn’t have been able to do any of those things had she started chemotherapy and radiation,” Diaz said.

We had to load up a U-Haul with all of our belongings, and she would say ‘Why do we have to drive 600 miles north, just so I can die peacefully?’ – Dan Díaz

On Nov. 1. 2014, Maynard took the life-ending medication in her bedroom of her Oregon home. Diaz said she fell asleep five minutes after drinking the medication. Within 30 minutes, her breathing slowed and she died.

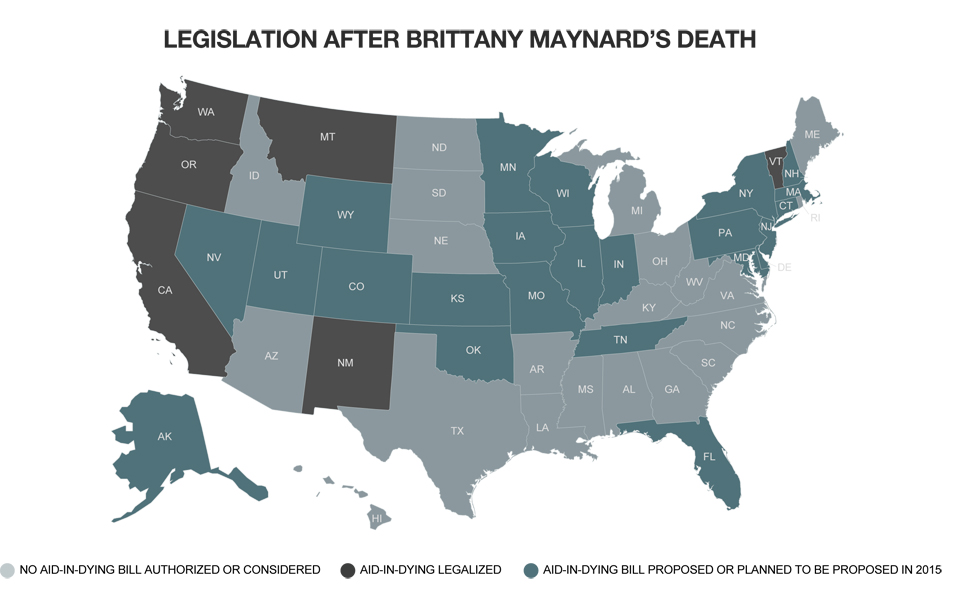

Maynard’s story was national news, and after her death, legislation was proposed in Washington DC and 20 other states. Leaders in Tennessee and Pennsylvania planned to propose similar legislation in the future.

Diaz said that before Maynard, aid-in-dying was seen as something for older people. Maynard was young and passionate about the issue, which caught people’s attention. “I think that’s what made the difference,” Diaz said. “People could look at Brittany and say ‘that’s me,’ or ‘that’s my spouse,’ or ‘that’s my sister.’ That could be anybody.”

In California, state Sen. Bill Monning (D-Carmel) and state Sen. Lois Wolk (D-Davis) introduced the End of Life Option Act in January 2015. Governor Jerry Brown signed the bill into law on Oct. 6.

The End of Life Option Act mimics Oregon’s law, which passed 18 years ago. No doctors or hospitals would be required to participate. Physicians who do participate would be required to explore other alternatives–like hospice care, pain management and palliative care–with their patients.

A patient wishing to request the medication must be competent, must be acting voluntarily and must not be coerced. The California law also specifies the following criteria for life-ending prescription eligibility:

– Two doctors must determine that the person seeking the prescription is terminally ill with six months or less to live.

– If doctors suspect the patient is depressed, they must recommend a psychiatric evaluation.

– The patient must request medication twice orally and once in writing.

– The patient must wait 15 days before he or she receives the medication.

– The patient must have two witnesses present when submitting a written request to the physician. Only one of the two witnesses can be related to the patient by blood, marriage, adoption, or inheritance.

– The patient must be able to sell-administer the medication.

Additionally, California has some requirements that Oregon does not. It specifies that if the conversation between doctor and patient is in a language other than English, a translator must be present. Wolk also said the law has strengthened protections for doctors prescribing the medication and added immunity for pharmacists who fill the prescriptions. Pharmacists who dispense the medication in “good faith compliance” with the law couldn’t be charged with neglect or elder abuse.

Proponents refer to receiving life-ending medication from a doctor as aid-in-dying while those opposed call it physician-assisted suicide.

George Eighmey, vice president of the Death with Dignity National Center, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting laws similar to Oregon’s, said suicide is when someone who is severely depressed but generally healthy otherwise decides he or she doesn’t want to live anymore. Eighmey said he has been at the bedside of about about four dozen ill patients. “They were always hurt when people used the word suicide,” he said. Oregon did polling that showed when the issue was called aid-in-dying, 70 percent of the population was in favor of it. But when the word suicide was used, support dropped to 53 percent, he said.

Many organizations took a formal stand against the law when it was proposed. Marilyn Golden, a senior policy analyst with the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund, argued that terminal diagnoses could be incorrect.

“The criterion of terminally ill with six months to live pretends you can make a distinction between that group and everyone else who is protected and safe,” she said, adding, “In fact, there is no way that is true, because the prognoses of terminal illness are wrong all the time.”

Many disabled people were misdiagnosed as terminal many years ago, she said, and some have gone on to raise families and have happy lives. “Before somebody learns what the quality of life could be, they could make a step that is irrevocable,” she said.

Other opponents of the law included medical groups, like the American Nursing Association, the American Medical Association and the Alliance of Catholic Health Care.

“It’s a common sense issue about what it’ll do to medicine,” said David Hammons, a retired emergency physician at Kaiser Permanente in Santa Clara, Calif. before the law was passed. Hammons was on the hospital’s ethics committee for more than 20 years, and is an active member of the Catholic Medical Association.

Having the option to end their lives could take away patients’ interest in pursuing treatment, he said, adding that it could encourage them to feel like their lives are not worth living anymore.

You have to look at the whole picture. What it’s going to do to society, what it’s going to do to petients, what it’s going to do to physicians. – David Hammons

“My opinion, as a physician, is that it would create more problems than it would help,” Hammons said. Health care coverage is also a major issue, he added, because life-ending medication is often cheaper than treatment. He said he’s concerned that physician-assisted suicide could become the only option available to those who can’t afford chemotherapy. “You have to look at the whole picture. What it’s going to do to society, what it’s going to do to patients, what it’s going to do to physicians,” he said.

Ned Dolejsi, executive director of the California Catholic Conference, agreed that the End of Life Option Act could have a potentially negative impact on society. The California Catholic Conference lobbies on behalf of the Catholic Church, which is one of many organizations that are part of Californians Against Assisted Suicide.

Dolejsi questioned how physician-assisted suicide could be the right of those with six months or less to live when it wouldn’t be the right for those who have a year or more to live, those who are disabled, and those who are depressed. “We can say this is all hypothetical, but I think it’s a very serious public policy question,” he said. “Once people start defining quality of life, they start making judgments about whose quality of life is worth it or not.”

There can’t truly be safeguards for a law that asks people to voluntarily report what they’re doing, Dolejsi said. “There’s no oversight,” he said of Oregon’s law. “We actually only know what the people who practice it want us to know.”

The Catholic Church is traditionally against assisted suicide. “God is God and we’re not,” Dolejsi said, explaining that God has given people the “gift of life,” that sometimes includes suffering. The Catholic belief is to be there for people who are dying and help them deal with their fears at the end of life rather than helping them end their lives, he said.

But Catholics aren’t vitalists holding onto life no matter what, he said. Rather, Catholics believe people should be able to choose to discontinue treatment if they’ve had enough or don’t think the treatment will benefit them. “That’s different than saying, ‘No, I think I will take my life right now,’” he said.

Dale Borglum has another spiritual perspective on aid-in-dying, though he’s not affiliated with any religion. He is the executive director of the Living/Dying Project, an organization that offers spiritual support for people with life-threatening illnesses and those who care for them. The project has volunteers working with nearly 1,000 people in a handful of San Francisco Bay Area counties, and since the 1970s, Borglum himself has worked with thousands of people near the end of their lives.

Some of those people have wanted to take their own lives, he said, and they have even asked Borglum for life-ending pills. Often, the same people would later tell him they were thankful they were still alive because they’d been able to grow spiritually. “At the same time, if somebody’s in pain and they can’t deal with it, I don’t think it’s my job necessarily to say, ‘No, you shouldn’t do that,’” he said.

Many of the issues brought up by people against aid-in-dying have not come to pass in Oregon, according to George Eighmey. “It’s been flawlessly implemented,” he said.

Eighmey, vice president of the Death with Dignity National Center, served on the Oregon House of Representatives from 1993 until 1999, where he was an advocate for the Death with Dignity Act that passed in 1994. The original Act passed with 51 percent approval statewide. A second statewide vote in 1997 made it legal to obtain lethal medication from a physician. In the 17 years since it became legal, more than 800 people have utilized the law, he said.

Opponents said Oregon would become “the dying state” and that thousands would move there to take advantage of Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act, Eighmey said. However, only one or two people move to Oregon from other states to take advantage of the law each year, according to Eighmey. Maynard was one of two people who moved to Oregon in order to die in 2014.

Opponents also said people could be coerced into taking the drug. But Eighmey said, in most cases, the dying person struggles to convince his or her family that dying is what they want to do. “They want them to live. It’s the dying person who says, ‘No. I’ve done it all.’”

I hope we can impact the law in time for me. But regardless of what happens to me, I want it for my family. I want it for the people I love. – Jennifer Glass

Another point of controversy arose over previous state coverage of lethal drugs. In two cases that occurred five years ago, dying patients on the Oregon Health Plan wanted the state to pay for their experimental treatments that hadn’t yet been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. In order for the state to pay for the treatment, the drugs must have had a 5 percent chance of extending someone’s life by five years.

In these cases, that requirement wasn’t met, according to Eighmey. The state sent the patients letters explaining that they would pay for hospice, comfort care or the life-ending medication. “Opponents said, ‘See, the state of Oregon is telling people to kill themselves,’” Eighmey said. The Oregon Health Plan no longer includes life-ending medication in its denial of coverage letters.

Jennifer Glass, an advocate for aid-in-dying in California, poses for a photo in her backyard in San Mateo, California.

Of those who seek assistance in ending their lives in Oregon, 95 percent have health insurance and 93 percent are in hospice care, he said. “They are getting the health care they need. They’re not being coerced.”

Aid-in-dying has been debated in California several times over the years. In 1992, the group Americans for Death with Dignity proposed a bill that would allow patients with less than six months to live the right to request life-ending medication from physicians. The measure failed with 45.87 percent of the vote. Lawmakers failed three times to pass bills between 1999 and 2006.

Polling from July 2014 showed that 64 percent of California voters supported aid-in-dying legislation. National polling, which was conducted after Maynard’s campaign in November 2014, showed that three out of four Americans supported aid-in-dying.

Both senators Wolk and Monning expressed that they believe aid-in-dying is a civil right. Wolk said she’s carried many meaningful bills, but this particular one has “struck a chord.” She said the mail she’s received has been overwhelmingly positive. “It’s pretty amazing. It means that people are dealing with this issue more and more,” she said. Wolk said everyone she talks to has a story about a loved one’s death. “It’s always the same statement, and that is: ‘it was really awful. There ought to be a better way.’”

One of the main proponents of the bill, Compassion and Choices, is a non-profit organization determined to making aid-in-dying accessible. The late Jennifer Glass of San Mateo, was an affiliate of Compassion and Choices, and had spoken up many times to advocate for aid-in-dying in California.

After a long career in Silicon Valley, Glass received a diagnosis of advanced lung cancer in 2013. She said she had seen the documentary “How to Die in Oregon,” and was interested in understanding all of her options, so she contacted Compassion and Choices as a client.

“It was the first time that I understood clearly, really, how hard it is to have a legally authorized, peaceful, end of life, if you have a terminal illness,” she said.

Glass went through chemotherapy and radiation for two months, which shrank her tumors. In February, she was taking Tarceva, an oral chemotherapy that kept her tumors from growing. However, she said her condition could change at any time.

“I know my life will end. I’m at peace with the idea that my life will end,” Glass said in February. “But how it ends, if lung cancer runs its course, can be brutal.” To Glass, aid-in-dying was not suicide. She emphasized that she did not want to die, and was doing everything she could to live as long as possible. “I want it desperately for myself,” she said of making aid-in-dying legal in California. “No one should have the right to prolong my death.”

I hope we can impact the law in time for me. But regardless of what happens to me, I want it for my family. I want it for the people I love. – Jennifer Glass

In June, her cancer returned. It had spread from her lungs to her liver, abdomen, cervix and pelvis. She also had a one-inch tumor in her brain. Glass tried one round of chemotherapy but found it “unbearable,” her widower Harlan Seymour said.

Even though she was ill, Glass wanted to testify at an Assembly hearing in July, Seymour said. But ultimately, it was cancelled. Glass died of lung cancer on Aug. 11. She was 52 years old. “I was lucky to be there. I was holding her hand and her cat was there too,” Seymour said. In lieu of flowers, Glass requested that donations be made to advocate for the legalization of aid-in-dying.

_____

*UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism